Playing Vampire Towns: Notes on “Sleeper”

Notes on “Sleeper” — Buffy the Vampire Slayer episode 7ABB08

Directed by Alan J. Levi

Written by David Fury & Jane Espenson

[ Previously on Buffy the Vampire Slayer: "Conversations With Dead People" ]

"The Sleeper will wake. The Sleeper will wake and the world will bleed."

—Luke, "Welcome to the Hellmouth" (1.1)

As an episode in and of itself, "Sleeper" is Season Seven worrying itself in circles. The plot is something of a detective story, with Spike inexplicably killing humans and serving as Monster of the Week. In the Buffy-centered strand, taking a tip from Holden Webster in the previous episode, the Slayer tails the vampire to determine if he's killing people. In the Spike-centered thread, the amnesiac retraces his steps to determine if he is a monster. All Buffy figures out is that Spike is killing people, it does not seem to be of his own volition, and that something bad, unidentified, and with direct access to their heads is meddling with them.

If we confine ourselves to “Sleeper” proper, there is very little to say about the plot, so we must skip ahead. The sitch is that The First Evil has hypnotically fitted Spike with a mind-control trigger which causes him to regress to his predatory demonic state. This brainwashing likely took place early in the season while Spike was raving in the basement of Sunnydale High, tormented by manifestations of his guilty conscience which were actually visitations from The First Evil. The problem with this is absolutely none of this is made clear in “Sleeper”, and some of it will never be made clear. Any reasonably attentive viewer will grasp a connection between Spike’s fugue states and appearances of the English folk song “Early One Morning”, and likely identify it as the Queen of Diamonds for this Manchurian Candidate. That turns out to be enough to follow the plot, though none of the characters will actually figure it out until the next episode.

The Buffy/Spike material is the only compelling story throughout Season Seven about romantic relationships. If there is another, it is likely between Xander and Anya. Both these stories are pure fallout and coping, rooted in relationships gone awry during Season 6; namely, they’re still dealing with the Spike/Buffy breakup and the cancellation of the Xander/Anya union (note: we do not use shipping nicknames in these parts, keep moving, hombre). Buffy, in essence, has no designated Love Interest this season, breaking tradition and pattern. Except…

While these pairings are old business in and of themselves, they are now the stories of exes in the process of negotiating reconciliation. Truce building stories, moving on stories, love stories about people who aren't exactly in love stories. Our third ensemble lead, Willow, is largely excused from duty in “Sleeper”, but her “love story” this season is also about the end of her relationship with Tara, more than it is about so-called new girlfriend Kennedy. Like Buffy and Spike, and Xander and Anya’s personal character arcs, that one’s about learning to care for yourself, to trust yourself, to put your broken shit back together and function, maybe even improve. One might further propose that everyone’s love interest in Season Seven is, really, themselves. Because if you didn’t notice, this is a show about growing up.

So this is a Buffy romance tale we have not seen before, at least not seen explored with any depth or maturity. While our hero is constantly having to deal with her feelings about Angel, those two are not to be resolved, not to be made stable, and never more together than when they are Officially Not Together. This is because Buffy and Angel kept apart by the very forces of the cosmos is the dramatic center of all Buffyverse romance; the Buffy/Angel they-can’t/they-must dynamic is the core of the mythos. As a very different iteration of Spike once explained, B and A will be in love till it kills them both (even though, of course, they have both already been killed). But we’re not here to talk about Angel, this is about Spike. And where Angel’s thing is to walk away in martyrdom, Spike’s is to constantly insinuate himself into unstable situations and sacrifice himself. So patching things up with Spike isn’t like Oz or Riley popping up for a one-off special appearance. Whether it’s the game of dueling undying torches with Angel or the moth-to-flame work-in-progress quest with Spike, they’re both long-termers, contractually bound to the very end, and once she meets them, they are woven into the fabric of her life.

When The First Evil promised in “Lessons” (7.1) “…we’re going right back to the beginning,” that turns out to mean, among other things, that several main characters will be forced to confront issues at the very core of their conception. We’re going to be looking hard at the wounds and wrongs buried deep in origin stories: original sins, traumatic births, first evils. For Spike, this arc is more or less initiated with “Sleeper” and resolved in “Lies My Parents Told Me” (7.17), and deals with how much of Spike’s sense of self-worth hinges on validation from the women in his life. This folds neatly into the Buffy/Spike reconciliation story, at least on paper.

The episode is all set-up, anomalous in that it isn’t self-contained in any way. Even the most stand-alone Buffy the Vampire Slayer episode is firmly situated in series continuity, and even the most serial-oriented episodes introduce and wrap up some kind of basic plot problem within the hour. This is a Spike episode, and no other character has gone through so many complicated transformations. Much credit to James Marsters for providing the poor lovesick demon with a continuity of character, as Spike is currently: 1) a vampire, 2) a slightly “different” vampire, having always retained some capacity for love, 3) physically unable to harm human beings, due to a violence-inhibiting microchip in his brain, 4) late in possession of his Soul, whatever that means, and was 5) driven (temporarily?) insane by that process. Thus has the matter of how much free will Spike has at any given point, and if he is really to be held responsible for his actions (positive or negative) has been contentious since Season Four.

The First’s plan (whatever that is) serves to bypass the various muzzles placed on Spike over the last five years, showing us Spike As Vampire again. This is Spike roughly where we first met him, another sense in which we have gone “right back to the beginning.” For those following along on your scorecards at home, the musical hypnotic trigger is #6, cutting through Spike Exceptionalism Items 2—5.

“… a person needs new experiences. They jar something deep inside, allowing him to grow. Without change, something sleeps inside us and seldom awakens. The sleeper must awaken.”

—Duke Leto Atreides, Dune

In “Bring On the Night” (7.10), once they've more or less figured out what's going on, Buffy will call these journeys into highly personal beginnings “[facing] our worst fears,” even if it turns out to be more complicated than that. “Sleeper”’s premise is established at the end of “Conversations With Dead People”, where Spike is seen picking up a blonde at The Bronze, walking her home, biting, drinking and killing her on the front steps. This thing, he should not be able or inclined to do, and The First’s trigger provides a scenario in which for all his striving to be a better man, Spike remains nothing but a soulless, irredeemable monster. That is one sense in which the Sleeper awakens. The murder in “Conversations” is depicted as a casual hookup gone horribly wrong; it’s staged as a seduction that erupts into date rape. This seems specifically designed to evoke Spike’s attempted sexual assault on Buffy in “Seeing Red” (6.19).

Spike, on his own trail and therefore on a quest of self-revelation, gets to see himself from an outside perspective. He encounters one of his recent victims in The Bronze but doesn’t remember her. Doesn’t remember killing her. Doesn’t remember siring her. What is this? “One bite stand,” she tells him, if this weren’t underlined enough. This isn’t just about Spike’s capacity for murder. The blackout episodes are also explicitly linked to his love life. He has either attended his relationships with a casual disregard (Harmony, his date to Xander’s not-wedding) or white-hot obsession (Cecily, Dru, Buffy), and either way it’s always about him.

To Buffy on his trail and still trying to get over him, it looks like Spike is lapsing, whether or not he’s vampire-relapsing. When the bouncer at The Bronze tells her that Spike is a player who “every night leaves with a different woman,” she’s hurt, and there it is. Hurt for the run-of-the-mill reasons, and disappointed that maybe all the rumor and accusation was true, and this motherfucker hasn’t changed at all. Maybe she was one of those projects to which he dedicates himself with insane abandon, the latest model in Spike’s century-spanning Slayer fixation, and his quicksilver amour fou has shifted already.

The next time Spike is called a Bad Boy it’s in an alley, so we’re back there again, at the most primal of Buffy scenes. This time he’s lured a woman into the dark recesses of the 3rd Street Promenade, it’s set up like another skeevy pick-up job, and she’s posing the question as they enter the battleground: “Are you a bad boy?” That’s the matter at hand, and our fully customized and kitted-out Season Seven Spike resists biting her, but it’s Rebooted Evil Spike in this round. Buffy is there, too, somehow, and she’s egging him on: “You know you want it. You know I want you to.” That’s all it takes. We know this is not really Buffy because she is acting transparently evil. The tactic is interesting, though. If The First is trying to seduce or provoke Spike, under what circumstances is “you want it/I want you to” what he wants to hear? It’s the kind of language he used in “Fool For Love” (5.7) to describe the intertwined fates of Vampires and Slayers like they were celestial bodies bound in orbit. This is the guy who thinks he and Buffy are partners in a turgid supernatural danse macabre while he’s actually usually sprawled on his ass in the alley, beaten-down. Love’s Bitch eternal.

OK so we’re going down to the basement. There’s a lot of that going around, lately, but Spike has a long, rich history of association with basements. He tends to wind up in them when his inborn villainy is flaring up, which makes sense with the subterranean thing and all. But a basement, an underground government lab, a lushly furnished sex-lair, a labyrinth beneath a school — they’re not quite graves, but specifically basements. Sometimes he retreats there, sometimes he’s forced, sometimes he crashes through the ceiling because he is a dumb guy of easily enflamed passions. They’re id-spaces, downstairs-inside places where he sometimes goes to chain up girls to make them like him, or sometimes to win back his own soul, and for better or worse (really, for better), he emerges transformed.

Oh, right, so: Brainwashed-Spike has been planting corpses in the basement of a suburban house. They’re all timed to rise at the same moment (?), when Spike brings Buffy downstairs and The First sings the trigger song and then away we go. The First’s plan appears to be to send Spike back to the basement and to drag Buffy with him, to force her to see him like that. The First will debase them both, and Spike will bite her, signaling that everything is lost, he’s gone blood simple and maybe one of them dies, who knows, who knows if it matters. When she sees this, will she wonder — is that all we were ever doing? Not dancing, but killing each other? Was he just dragging her down to the basement this whole time? Down there they could cocoon up and wound each other the only way he knew how. The only way, ever since that false-soul brain chip came and made him dishonest, made him cunning, a masochistic beast on a leash who loved it when she jerked him around until the day when he would inevitably bite her. Was he using her? How could he! That’s what she’s supposed to see. That’s the plan, but…

Maybe he's simply overwhelmed by searing guilt of being recently used like a common Dollhouse Active in a serial murder rampage. But the basement attack, with Buffy held down by vampires and Spike looming over her, seems to trigger reminders of the bathroom assault in “Seeing Red” and he recoils — “I remember” — and stops. How, after all, could he use a poor maiden so? The mechanics of how Spike breaks through the conditioning don’t make much more sense than how he got brainwashed in the first place, but the lesson is plain. If you can’t abide the convoluted history of Spike’s development, if you want Old Spike back, well… first, what does that mean? How far should he regress, or when should he stop striving? And if you want him back as we met him, here he is (minus Drusilla), but does that really even look like Spike anymore?

When Anya calls him a bad boy it’s silly — a joke. Under his own power, naked in her bed with Anya on top of him, Spike is kind and even lets her down easy. This is the guy we recognize as Buffy’s boy, not the monster in the alley, not the thing in the basement. From this angle, outside himself, Spike has been able to observe that this is not “him” anymore. Not the casual dalliances, certainly not the murder. By the time we get down to the basement where all the horror and shame lives, it’s not even his basement, properly, and those old bad boy patterns don’t make him happy, they hurt other people, and are, now, beneath him. Yet somehow, with and without the soul, he’s always owned up to who he is and what he has been, so it’s about something else: “As daft a notion as Soulful Spike the Serial Killer is, it is nothing compared to the idea that another girl could mean anything to me.” This “worst fear” is also that this is how others see him, specifically how one person sees him, and God help the boy, it’s still all about Buffy.

And ultimately down in the basement, she sees through it too. He’s pled his case, she's examined evidence, witnesses, etc., and finish that one yourself. In the next episode she will say that she’s seen him change. Here in “Sleeper” she doesn’t need to say it out loud, but when he’s brave enough to ask for her help, she agrees without hesitation and we cut to Spike swaddled in a blanket. In her home. That’s the thing about basements. They’re underneath something, below a structure, and if you climb the stairs you are among the community again.

“In the end, we are who we are, no matter how much we appear to have changed.”

—Giles, “Lessons” (7.1)

This is all a slow build to formative incidents centered on Spike’s siring which are revealed/confronted in “Lies My Parents Told Me”, and the story is built backwards, burrowing through Spike’s lifetimes to locate the developmental traumas of his second childhood. But we don’t explain and solve Spike by getting the details on his mommy issues. Maybe it’s more important that we just learned something here and now about Spike as he exists in the here and now. So he’s back in the living room, and it’s cozy scene, no? Spike’s tied to the chair, of course. Because they still might have to kill him for his own good.

There’s not much discussion on that front. The household has convened and everyone is uneasy, but she’s obviously not going to kill him. Right at the moment his case is buffered as he’s the only clue they have about the thing that turns out to be The First Evil. No, this is a quick one about whether to keep Spike in the house. Xander, Anya, Willow and Dawn note that Spike’s clearly a danger to others, for example the ten people he just killed. If you write those books that use BtVS to illustrate philosophy lessons, now is the time to point out that preschools are not morally obligated to take in every starving Rottweiler on the street. But the deck is stacked here, too: they can’t (or won’t) kill him, and they can’t leave him alone. The issue is basically raised in order to sell the idea of Buffy bringing Spike home but doesn’t put the plot to bed. The divide is about Spike in general and Buffy’s judgment in particular; it’s about trust. So the scene does reestablish the factions in this conflict, and those are basically Buffy and Spike versus everyone else. No new business today. Buffy is soft on ensouled vampires. This is the fracture that never heals entirely.

In the end, it does not appear that The First intended for Buffy or Spike to die in the basement. The details of that master plan remain forever unclear, and ultimately it will look like the villain is simply lobbing every available attack at the Slayer until it manages to draw blood. Pitting guilt-racked exes against regressed, primitive versions of each other is exactly the kind of tactic The First used against Willow, Andrew, and Dawn in “Conversations With Dead People”. It tugged at loose threads of insecurity and each of them is going to unravel in turn. The shadows of fault lines are appearing in the topography of the greater Hellmouth area.

Speaking of guilt, there is an abundance hanging over everyone’s head right at this point. The full implications of the folk song are laid out in “Lies”, but “Early One Morning” itself is accusatory. “Sleeper” links it to the season-long back-and-forth between Buffy and Spike about who “used” who. The song is set “just as the sun was rising” over “the valley below”: the maiden’s lament is literally emanating from a Sunny Dale. The musical trigger was foreshadowed by First-as-Drusilla in “Lessons”: “You’ll always be in the dark with me, singing our little songs,” it purred to Spike. “You like our little songs, don’t you. You’ve always liked them, right from the beginning.”

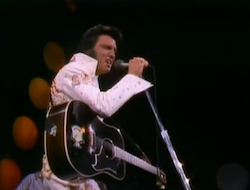

Besides that haunting trigger melody from Spike’s past, “Sleeper” prominently features two Aimee Mann songs from her 2002 album Lost in Space. Appearing in person and on stage at The Bronze, Mann’s performance is intercut with Spike in the balcony chatting with his “one bite stand,” and the show continues even when the kickboxing starts and vampires are falling from the sky onto the dance floor. Both songs, “Pavlov’s Bells” and “This Is How It Goes” resonate with the hypnotic trigger theme. They are concerned with feeling trapped, bound to repeat mistakes, locked into automatic psychological response cycles, stuck in fate’s web. They are also both about feeling bad about yourself, and the editing practically elides the entirety of “This is How It Goes” into one emphatic “hallelujah” from the chorus: “IT’S ALL ABOUT SHAME!” Spike will soon observe of possessing a soul that “It’s about self-loathing” (“Never Leave Me” [7.9]). Maybe there’s something to that, or maybe there’s a little more to it than that. Let it never be said that Spike has no more room to grow. Trotting offstage, Aimee Mann grumbles “Man, I hate playing vampire towns.” I’m sure it’s a drag, but if only she could see how much she resonates with them.

A final note before we let our sleeper rest in peace. Minus the cold open, the episode is bookended by a pair of puzzling cliffhanger snippets. In a well-appointed flat in London (London, England), Robed Figures murder two folks we likely infer are another Watcher and Slayer-to-Be (spoiler: they are). They do not return until the end of the episode. Giles enters the place we don’t know and finds the bodies of the people we don’t know and suddenly Robed Figure (as per the script) “SWINGS A DOUBLE-BLADED BATTLE AXE AT THE BACK OF GILES’S HEAD,” roll credits. A kind of hackneyed surprise, but a surprise. This is all a little out of nowhere, or at least of hazy origin, and doesn’t resolve anything or reveal much, which in its way makes it a perfect set of fore and aft epigraphs for “Sleeper”.

* * * * *

All screen caps courtesy of Buffyworld.