Saturday, December 25, 2010

Thursday, December 09, 2010

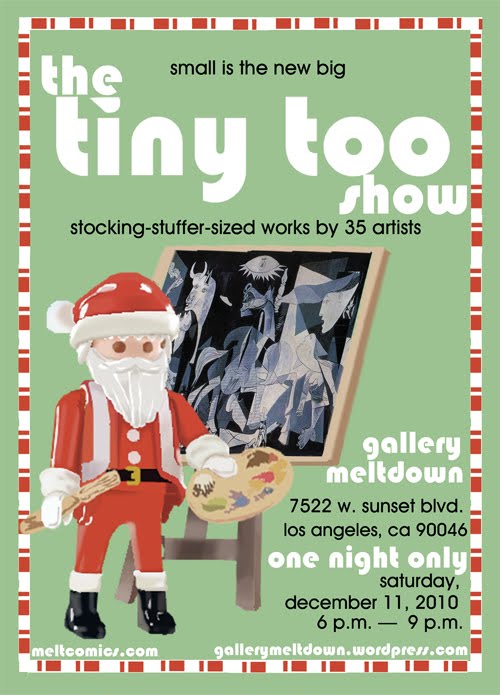

TINY TOO Art Show Announcement / Wallet-Size Kaiju

The TINY TOO SHOW exhibition at Gallery Meltdown showcases eensey-scale work (three inches or smaller) from some thirty-plus artists. Yours truly will also be in the show, and as per usual, the peripheral reason to mention this here is that my pieces are movie-culture-related. As the show is a one-night-only, cash-and-carry affair, the bulk of the art is available for perusal and purchase in the preview catalogue <— linked right here. Among these little gems is something for every budget, and as they take up less wall space than a commemorative $2 bill, make excellent holiday gifts. Direct purchase inquiries to Gallery Meltdown staff, at the links above/below, in person or by phone.

The TINY TOO SHOW goes up on December 11, 2010 from 6 P.M. to 9 P.M., in the gallery space of Meltdown Comics, 7522 W. Sunset Blvd., 90046. Those peculiar persons for whom Wednesday is not synonymous with "New Comics Day" often ask "Where on Sunset is that? I've never seen that," and the answer is "West Hollywood, somewhere between the In-N-Out and that Griddle Cafe place that cooks Oreos into pancakes."

So below are photographs of my tiny paintings, which depict beloved monstrous creatures from Japanese tokusatsu media. That is, they're all guys in rubber kaiju suits. Each of these oh-so-ironically mini-kaiju are acrylic on 2"x2" MDF. As disclaimer, in person these are considerably more lustrous, not so washed out, and appear less "blotchy" and more "pointillist," as digital scanner or camera simply cannot convey the miniature-ness on hand. Anyway, do consider that you're seeing these rascals at nearly twice their actual size, which completely undoes any in-person effects, but is fun anyway. Away, then!

Front of the pack, but the most modern design of the bunch, Godzilla's first giant monster foe appears in approximation of his Destroy All Monsters! design. Anguirus' 1968 incarnation was selected over his First Appearance look in Godzilla Raids Again (née Gigantis, the Fire Monster, 1955) because 1) I love Destroy All Monsters!, 2) the film is in color, which avoids having to paint in monochrome or inventing a color scheme for the beast (the original suit is rumored to have been painted in hues of red and blue!), and 3) later appearances do not try to mask that the design forces the suit performer to crawl around on hands and knees. There is, in my opinion, something charming and a little magical about bent-knee kaiju, a necessary acquiescence to the anatomical reality of the actor, a silent signifier of the Real World that could break the illusion but that is, instead, gradually absorbed as a genre convention. Blessed are the knee-crawlers.

The most esoteric of this cluster is Kanegon, who appeared in the Ultra Q episode "Kanegon's Cocoon". Despite having featured in one TV show more than forty years ago, the coin-purse-headed, non-giant kaiju is a readily recognizable icon in his homeland, and is steadily reproduced in vinyl and resin of all size and color. The excellent Ultra Q has sadly never been exported to America, but is available on nice, ultra-pricey Japanese DVD from the usual sources for such things. Naturally it's never been dubbed or subtitled, but you don't entirely need a translation, particularly for this kid-logic fable about the dangers of money lust. Briefly, greedy boy Kaneo finds a pod full of coins, is sucked inside, and wakes up as a Kanegon, which must eat cold hard cash to survive. With some familial resemblance to "The Metamorphosis" and Carl Barks comics, the episode finally goes full-on weirdo in the dénouement, where Kanegon somehow blasts off into space, Kaneo parachutes back to earth, and finds that his parents have turned to Kanegons, too. Anyway, the episode contains several indelible images, including the desperate creature crouched curbside before a dropped safe box and shoveling coins into his maw, as well as one of the more hair-raising stunts I've ever seen, when the suited Kanegon actor falls from a moving bulldozer and into the path of the blade. But vague morals about greed and alien ass-rockets aside, I suspect the episode endures because of a single lyrical shot of the lonesome Kanegon sitting on a quarry hillside at sunset, gazing into the distance.

As re: the painting, I cop to having backed off on the backlighting and dusky shadows of this scene, in exchange for a clearer look at this classic monster suit. Relatively trustworthy color documentation exists, but I chose to depict the scene in Ultra Q-accurate black and white.

Mothra comes at the suggestion of the lady of the house. Good thinking, since girls like Mothra, and a request I'm glad to fulfill because she lets me keep dozens of vinyl monsters in the living room. Besides a hindwing reduction and proboscis redesign after her 1961 debut, I don't believe that Shōwa Mothra underwent drastic changes in look. Like everyone else, I try to keep up on these things, but claim no expertise.

The scene in the little picture above comes from her '64 appearance in Mothra vs. Godzilla (Godzilla vs. the Thing, for the elderly), as the aging Mothra takes refuge in her sacred cave on Infant Island and rests up for one final, self-sacrificing battle. Mothra has, the Infant Islanders say, chosen to defend Japan against Godzilla, though her life cycle is ending and human greed has endangered her massive, beached egg. There is a quiet majesty to this scene that seems intrinsically Japanese — being, as it is, about natural cycles and personal sacrifice for the good of society. Overhead light streams into the dark cave and rims the beast's gently flapping wings, a melancholy wash of mono no aware clarity and beauty all the more unexpected for being in a tale of giant monsters amok.

This is among the most moving and delicate scenes in a Godzilla picture — if not top of the list — and one of the many elements that recommends Mothra vs. Godzilla as a particularly fine installment.

I've cheated the angle of Mothra's wings, and fudged the interior of the cave, for more dramatic (and square) staging. Do forgive me. And finally, inevitably...

Speaking of Mothra vs. Godzilla and its excellent qualities, the street-level story is funny and compelling. Theme park developers claim ownership of Mothra's egg, the working class fishermen who discovered it demand compensation, career politicians try to put positive spin on disasters, and newspapermen have honest-to-God ideological discussions about the degree to which journalists should shape public opinion. That's just a random sample of this idea-rich masterpiece, and Mothra vs. Godzilla is exactly the counterattack to keep in your arsenal when some chucklehead tells you that a Giant Fighting Creatures movie mustn't/needn't/can't/shouldn't aspire to be anything but stupid, loud, cinematically incompetent, etc. You will need this weaponry in the near future, likely in battle with the Transformers franchise.

Back to the point, MvG also sports one of the very best Godzilla suits, affectionately shorthanded by enthusiasts as Mosugoji, and pretty much the hands-down fan favorite Shōwa suit. Personally, I can't help but feel the most affection for the Soshingeki-Goji of Destroy All Monsters! through Godzilla vs. Gigan/ on Monster Island, and there's something abominably creepy about the King Kong vs. Godzilla suit, but in the end, I cave to popular opinion on this one.

As for the King of Monsters half of the equation, Godzilla is depicted as an irredeemable asshole in the film, is given one of the all-time, any-movie greatest entrance scenes, a delightfully ignoble comeuppance at the end, and...

In the above scene, Godzilla slips and smashes into Nagoya Castle, then takes out his rage on the landmark: the coolest Godzilla design lays into one of the Tsuburaya Dept.'s most spectacular miniatures. Ironically/hilariously, restoration of the historic building had just been completed five years prior. So, obviously, that's a good, excruciatingly laborious thing to commemorate in a two inch painting. I can only add that I was a little bummed that to fit both the beautiful creature and castle the scale is such that one can't quite make out the golden dolphins atop the building.

P.S., the painting will be of Guiron from Gamera vs. Guiron. Because his head is a knife.

- Chris Stangl at 4:48 AM 0 comments

Indexed in: Godzilla, Ishiro Honda, kaiju, Los Angeles, pretty pictures

Saturday, November 20, 2010

Fox and Sam at the End of the Road: THE X-FILES and "Closure"

It is something of a joke, irony or, perhaps, stunt, to call an X-Files episode "Closure". Firstly, it shares the title with an episode of Millennium, part of a series of crossover and bounce-back between titles of the semi-shared Ten Thirteen Productions universe. Secondly, obviously The X-Files doesn't do closure. Certainly not in the narrative or business senses of the word, where the plot is an endless hanging garden of dangling story threads. The program's picture-making form is driven by denying visual closure. Beasts and bodies are concealed in partial shadow, angels and aliens blaze with intolerable light, and the signature images are two flashlight beams searching about in darkness and a cigarette cherry flaring in the murk. Nor does the show traffic in the sort of psychological "closure" (foothold in our pop psych lexicon gained during X-Files broadcast years) that the episode purports to deliver.

At its foundations The X-Files lacks epistemic closure, every moment is forever open-ceilinged, shifting and frustrated. Paradoxically, it is a closed loop and always was, relates back, receives information, and speaks meaning only to itself. But if you want my opinion, The Truth is both: The X-Files is deeply, deeply anxious, and obscurationist at heart.

Now then, the matter at hand is the ultimate fate of one Samantha Mulder, disappeared from her family home at age 8 in 1973, and the resultant impact on the mental state of her brother, Fox. Because The X-Files is an elegantly constructed machine, one thing leading to another and all, the curious circumstances of the abduction witnessed by the elder Mulder sibling provide meaty story materials and internal character psychology, both. Plainly, when we meet Agent Fox Mulder in 1993, he has come to believe Samantha to have been swiped by marauding aliens. The knight's quest to locate the absent sister fuels much X-Files narrative, and as it is, in short order, folded into the larger series-long mechanics of the Syndicate conspiracy and the antics of various space peoples, a story element of central, driving concern. What Happened to Samantha? is not just juicy Mulder backstory, but frontstory. Forward-story.

Even when not directly inquiring into Samantha's whereabouts, whether tackling concerns larger (global Martian invasion) or unrelated (vampires, mutants, chupacabras), she looms large in Mulder's headspace. Sam is riding on Fox's shoulder and just over the horizon as he chases every Jersey Devil down every blind alley. The memory of witnessing the abduction and the pain of loss catalyze a perfect chain-reaction leading to the Mulder we know: a propensity to regard the paranormal with credulity, a paranoiac bent, empathy for victims, a martyr complex, and so on. Perfect, that is, but for the absent center. Mulder's psychology and belief systems whirl around a cavernous gap and he might collapse in on himself at any moment. He is a man built on shaky premises. Two vital supports that (usually) prevent implosion, though they tend to contradict one another: Scully's devotion to keeping him in check, and repeated evidence that tells Mulder he is right. The kind of closed-loop logic that runs Mulder — no one believes me-> I will make them believe by solving X-Files-> no one believes me because I investigate X-Files — runs all the way down on the basement level of the character and the series. This simple hook with convoluted barbs is summed up by that despairing/hopeful kōan: "I Want to Believe."

So then, the true tale of Samantha's fate and the passion of Fox Mulder: these are the entwined snakes to which episode 11 of season 7, "Closure", intends to bring closure. At the end we will hear an explanation, and Mulder will mutter, "I'm fine... I'm free." But maybe the explanation is not an explanation, and maybe Mulder is neither fine nor free, and just maybe there will be no closure. Then again...

I Saw the Sein

Besides a loathing of plot summaries, a guided walkthrough of the episode is perhaps not the cleanest path through these muddy waters. On first pass, "Closure" seems meandering, its conclusions confusing and confused, to say nothing of dissatisfying and, well, inconclusive. These things may be true, as there seems to be something wrong at every turn, but on the other hand something is wrong at every turn. After much gallivanting around Sacramento suburbs, a women's prison, an abandoned military base, and a fictionalized version of the Skyforest, CA Santa's Village park, a solution to the Samantha Problem. "Closure" says: Samantha T./A. Mulder was stolen from her home, then raised along with Jeffrey Spender at April Air Force Base by the Cigarette Smoking Man. She was likely brainwashed and made subject to medical testing until she escaped and was brought to an emergency room. Before Cigarette Smoking Man could retrieve her from the hospital, Samantha was (fortitude, people...) rescued by benevolent spirits made of starlight, known as Walk-Ins. The means by which the Walk-Ins save the souls of innocents about to suffer brutal, unjust deaths, is to (150 episodes and a feature film leading to this moment) kill them and make their bodies disappear without a trace.

To this information any reaction is acceptable, but popular candidates include "lame," "that sucks," and "holy shit." Sure, sure and sure, but only in flatly stated summary, because "mercy killed by star-souls" is less than half the story; it answers the What and When but not the Why and How. One troubling thing about "Closure" is that it sees the agents chasing down a lot of information that they have already discovered, as if reiterating the plot thus far for newcomers. So Scully reviews videos of Mulder's regression hypnosis from 1989, Mulder finds evidence that Samantha had been relocated to the Spender household, and the possibility is floated that the girl was victim of an entirely unrelated serial killer. None of this is news to the characters, none of it is entirely new plot material, but it forces all involved to sift through most of the open-ended possibilities yet again. Mulder pays multiple visits to the same abandoned house on April Air Force Base with reshuffled agendas, hours of videotape are pored over, mountains of hospital paperwork shoveled through, moldering secret diaries scrutinized, obscure witnesses tracked down and dozens of graves laid open. The treadmill churns, and, feet pounding the same few inches over and over, Mulder never lets up.

The X-Files has an ambivalent, relativistic relationship with the concept of truth. To say that "The Truth is Out There" implies a lot of things, including that one is therefore not in possession of that truth, that if it is perpetually "out there," that one cannot know it fully, but perhaps, too, that there is such a thing and a search may not be in vain. For central example, the truth of immediate concern and contention in any given episode tends to be whether or not some kind of supernatural jive is going down. There generally is, of course, paranormal activity afoot, and the audience is nearly always given some kind of "objective" — that is, not filtered through a character's subjective point of view — evidence of such. As such, it might seem that Mulder is nearly always right, while Scully is beating her head against a wall of irrelevant skepticism. It may further seem that The X-Files plays fast and loose — or "cheats," if you prefer — with this phenomenon, implying that there may be some other interpretation, forgetting what it has shown us, or, specifically, regularly allowing Scully to witness the paranormal but not to overhaul her worldview accordingly. A common complaint, that, but it comes a) from viewers outside the narrative, and b) as occasional gripes by Mulder.

The issue laid out before the characters — and the audience — is less about whether the world is swarming with ghosts and UFOs than it is about what one does with the information before one's eyes. When faced with evidence of Possessed Serial Killer #258, or even supernatural phenomenon that might comfortably fit into her belief system, as when visited by a cherub in "All Souls", Scully neither shuts her eyes and forgets it away, nor jumps to conclusions. She tries to assimilate that data with extant scientific knowledge, and when unable to do so, will admit she does not know what to make of the event. Mulder occasionally doesn't know either, but more often, faced with the same evidence, simply confirms a conclusion that he has already reached. Mulder and Scully are not symbolic stand-ins for larger concepts — e.g. Scully is not Science or Skepticism or Rationality — but characters with varied, contradictory and complex attitudes and qualities. The series' core subjects are the nature of truth and power, faith, religion, of science, belief, spirituality, the shaky narratives of history, nation and identity, so on, so forth — life and death stuff, as it were. The X-Files does not preach or lecture on these matters. It investigates.

"Closure" is the second half of a two-parter, following "Sein und Zeit", which is named, in the German, for Heidegger's Being and Time. The titles give a clue on how to read the episodes, "closure" in its multiple senses stands in contradiction to — but gaining reinforcement in its ironic inverse — reference to Heidegger's study of hermeneutical phenomenology. Now, pardon my butchering of an unsummarizable difficult work, but the relevant concepts in Heidegger would seem to be that a being's inquiry into the nature of being is perilous, cyclical and likely unending. A self-conscious being, by asking such questions, is in nature the thing about which it is inquiring. Absent external frame of reference, interfacing only with beings in the same situation, and wrestling with language that has a different being from that which it describes, a being can only gain understanding through systematic interpretation. The being is defined by past experiences, and while aimed at the future, that future, too, is shaped and framed by the perceiving being in terms of past experience.

This is more than enough to chew on as regards Fox and Samantha Mulder. Having already explored the ways in which Samantha's abduction in the past determines Mulder's present, is sure to define his future path, in its way is rather synonymous with his person, the remaining key concept seems to be the cyclical, incremental progress of understanding. The two-ep arc is about nothing if not dogged reexamination of evidence, paths in circles, arcs retraced until one being reaches some knowledge of himself, and therefore another being, and therefore Being. Halfway through "Closure", after weeping over a reading of his sister's newly discovered secret diary (it ends inconclusively), Mulder stands in a late night diner's parking lot. He sees...

... The void, penetrated by glittering pinpricks of light, which leads to this speechifying:

MULDER: You know, I never stop to think that the light is billions of years old by the time we see it. From the beginning of time, right past us, into the future. Nothing is ancient in the universe. But maybe they are souls, Scully. Traveling through time as starlight, looking for homes.

History, then, coalescing in a brief Now that is soon to be past, a history that was once future, a future always in the present. Time spacialized, existence as never ending search. A universe both lonely and sparkling in harmony, a dark space and a light on an unfulfillable quest. This from cold facts made into the sort of New Agey sentiment that stokes Mulder's fire and brings him a peculiar comfort.

"Don't look for it, Taylor!"

Earlier in "Closure", a portent. A certain ape gives advice to a certain spaceman in Planet of the Apes, playing on a motel television, "don't look for it, Taylor! You may not like what you find." Its function, 1) as a hint: this is about time, about looping back to where you began, about the grieving process, and 2) as a warning: perhaps not to Mulder, but to the dedicated, difficult-to-please audience. We are going out on that beach, an answer will be found, and, well, no guarantees after that.

To spend any time in the presence of diehard fantasy audiences — "fans" if you prefer, "geeks" if you absolutely must — is to find that they tend to possess memories for minutia like steel traps, a literalist streak and a contradictory apologist streak. Since we may not like what we find and The X-Files seems to know this, we ought to figure out why we may not like it. So, starting at the end and meandering around again, the Samantha File closes with the Walk-Ins. The Walk-Ins are problematic because they have never been referenced before, will never be heard from again. Their participation in the Samantha mystery has not previously been seeded and they yield to no rules of the fictive universe, and scoot in at an oblique angle to the established narrative facts; that is, amidst the warring government conspiracy, alien factions, serial killers and Feds, angelic star-ghosts can kind of do anything they want.

Perhaps, if these irritants can be weighted, the Walk-Ins' greatest offense is to introduce supernatural element to the central Mytharc storyline. Though The X-Files participates in and/or grabs elements and inspiration from dozens (hundreds?) of speculative fiction subgenres, the Mytharc has always been strictly science-fiction espionage thriller. A fine line, perhaps, but one consistently drawn: no magic in the Mytharc.

Finally, we may reject the Walk-Ins because they are brazenly sentimental in concept and execution. Color desaturated, double-exposed, and bathed in a shimmery glow, moving in uber-serious slow-mo, the little star-ghost-angels frolic as Moby's choir-and-strings piece "My Weakness" plays, and inspire much earnest Mulder monologuing. In their presence, a lot of discussion of the inherent innocence of children, the sort of Problem of Evil discussions that assume the presence of a watchful God and end up framing the spirits as holy agents. The specific language in the voice over is pure Mulder in sentiment, but uncharacteristic in that it speaks at length about "God," and along with the "My Weakness" sequence is highly problematic as it implies that it is a lovely thing that the purity of murdered children has been preserved in amber for eternity. The Walk-Ins, then, seem something of a cop-out, and a sappy cop-out at that.

The potential complaints about the Walk-Ins are, however, the very reasons they possess a bit of an edge and nuance that makes them harder to dismiss. "Believe to Understand" — "Crede, ut intelligas," as Scully could likely explain — urges the title card over that gloomy mountainscape where the banner usually reads "The Truth is Out There." There is that Augustinian inscription on how to read "Closure", and as it unfolds, Mulder is repeatedly warned off his search by the three people with whom his life is most closely intertwined. Scully, his mother, and Cigarette Smoking Man in a private Dr. Zaius chorus tell Mulder not to continue pushing for answers. But why?

The Infinite Samantha

Mulder has, as those paying attention know, been reunited with his sister several times, or, more accurately, been confronted with her physical presence in increasingly disconcerting form. Each iteration of Samantha branches out into new possibilities at least as much as it sheds light on the situation. This begins in "Colony" (season 2, episode 16) where Samantha returns to the family, only to multiply exponentially in the episode's continuation, "End Game", where she is revealed as one of several clones, and an alien hybrid. This effectively solidifies the link, in literal terms, between Samantha and alien activity, and in a more nagging, unscratchable way indicates to Mulder that if he solves one, can solve the other; naturally, having gotten this close, the slate is wiped: though no real "Samantha" is found or erased, the clones are all destroyed, yet Samantha-possibilities have proliferated before Mulder's eyes.

Next contact is made in "Paper Clip" (3.2), when the agents uncover a subterranean cache of abductee information, including Samantha's file (once marked for Fox) replete with "recent tissue sample." So there but for the grace of a 3M stick-on label goes Fox Mulder, reinforcing his survivor's guilt, doubt about his parents, and the caprices of circumstance: it could have been, almost was, eventually will be him. He has located a scrap of Samantha's body in her tissue sample, the smallest confirmation that she is alive, or was recently. Closer by inches.

The season 4 premiere, "Herrenvolk" (4.1) leads to an apiary tended by an army of eight-year-old Samanthas. But clearly they are clones — drones, even, barely able to communicate — stalled at the age of abduction. A reminder, here, that for those who swiped the girl, she was a tool with a function, and that for Mulder, the lost sister is irretrievable; he is chasing the idea of Samantha, and even if she is recovered, she will not be in the same condition as when she last played Stratego.

Apparently tangential, but straight in line with these replicating hypothetical Samanthas, is the season 4 episode "Paper Hearts" (4.8). The story explores the possibility that Samantha was a victim of child-killer John Lee Roche, and not taken by aliens, not with the involvement of the Syndicate, not with the forced hand of his father. The "Paper Hearts" concept will be floated again in "Closure". Both rounds, it turns up zilch. Roche even gives a full confession, which stands as the only complete, first-hand account of Samantha's fate... except that it is bunk. The source that appears to be yielding the most information is giving up the least. Again, odd (or discontinuitous) for Mulder to even consider this version of events after gathering (well, witnessing) so much counter-evidence. But he is open to possibility, willing to explore, and interested in dicey information, but not beholden to it, if it does not gel to his standards.

Finally, in the amazingly-titled "Redux/Redux II" (season 5, episodes 1/2), one more grown-up Samantha visits her brother. This time she is proffered as bait to lure Mulder from government work to shadow-government work, and believes the Cigarette Smoking Man is her father. With that, the final living Samantha disappears from the narrative. Fan speculation tends to agree that this was yet another clone, but all that is certain is that Samantha appears, spends an evening at home, Mulder does not take the Smoking Man's bait, and she is whisked away once more. Possibly the closest she's ever been, maybe he's almost got her back, and could be nothing happened at all.

As hinted, the crux of frustration and the masterstroke is that the "Sein und Zeit"/"Closure" diptych does not rewrite, overwrite or reconfigure exactly what happened to Samantha. The Truth of this matter, in hard, cold factual terms, is unaltered, and has been fairly firmly in place in most relevant details since, say, the fifth season. Mulder has known this for years, or more importantly, it is the version he believes, and the one we, the audience, also see with the most clarity.

Samantha was removed from Martha's Vineyard, as collateral in the Syndicate's dealing with aliens. On her return, she was placed in the home of the Cigarette Smoking Man, experimented on, and cloned several times over. This stands, Walk-Ins or no Walk-Ins. To these events, and while stressing the long-term project of the Infinite Samantha, all "Closure" adds to the known facts is: "She died."

The Smoke-Wreathed Heart

To Mulder's Zaiuses (Zaii?), then. All those concerned for Mulder's well-being take a turn instructing him not to pursue the Samantha matter during the "Closure" arc. Scully, most of all, has to deal intimately with her exhausted and tortured partner, and is attuned as to when to indulge, assist or put her foot down. She and AD Skinner have added motivation to keep Mulder in check, as he is chasing down Samantha via/at the expense of properly solving the child abduction case that spurred the latest tail-chase in the first place. They are right to worry, as by the end, the case is never properly solved.

More mysterious than the cares of Mulder's colleagues is the Cigarette Smoking Man's visit to Scully with a request: "I want you to stop looking." She will deliver a message, which Mulder dismisses with an accurate "Oh well, he's a liar." Sure is, and keep that in mind, but remember that when so inclined, the Smoking Man tells the truth like few others — a particularly cutting version of the truth because he understands relativism, that subjectivity, and agenda apply to all beings, himself included, and is up front about it. For that, Smoking Man scenes are always dense, and this one's a brief doozy. What the Smoking Man says is: "No one's going to find her... Because I believe she's dead. No reason to believe otherwise." Knowing the ending, and knowing that this is about "belief," note that CSM does not say that Samantha is dead or that he knows she is dead. While wrapped up in the suspense of first viewing, these comments are ripe with insinuation, and continue to spawn possibilities as the plot unfolds. Could be he killed her. Could be he had her killed. Could be he knows that she died due to "testing" — by the Syndicate or by aliens. Could be he suspects that, like his ex-wife, Cassandra Spender, the girl was abducted/returned/reabducted. Could be that he knows only what he saw, which is that Samantha disappeared from a locked hospital room just before he arrived. And now he has come to believe she is dead.

But this belief is not what CSM asks Scully to tell Mulder. When she criticizes his having withheld, er, whatever it is he knows for all this time, the Smoking Man explains, as he has before, as he will again: "Out of kindness, Agent Scully. Allow him his ignorance. It's what gives him hope."

Scully thinks about it. Scully doesn't seem to agree. Scully tells Mulder what Cigarette Smoking Man said. He is a liar, after all. "Mulder, why would he lie now?," Scully counters, and CSM had argued the same; that in previous years he was motivated to lead Mulder on to protect the Syndicate's secret work which was effectively destroyed during the season 6 "Two Fathers"/"One Son" arc. Why lie now? Well folks, somebody is lying:

"End Game" — BOUNTY HUNTER: She's alive. Can you die now?

"The Blessing Way" — (somewhere on the astral plane or something)

MULDER: My sister? Is she here?

BILL MULDER: No

"Two Fathers" — SCULLY: Agent Mulder told me he believed he saw his sister. Last year.

CASSANDRA SPENDER: That wasn't her, Agent Mulder.

MULDER: Then where is she?

CASSANDRA SPENDER: Out there, with them. The aliens.

So from abductees to apparitions to aliens, the weirdoes of the universe seem to believe Samantha Mulder lives and breathes.

Speaking of misleading information, Mulder's mother, Teena, in typically enigmatic form, shows up a handful of times during this chapter. She has always been more withholding than even Cigarette Smoking Man, and her tendency to occlude information hangs like a pall over the episode. She first appears while Mulder is away in California on a case. Alone at home, Teena burns a photo of Fox and Samantha, leaves a voice mail for her son, asking that he call back so she may discuss things "that I've left unsaid for reasons I hope one day you'll understand," and commits suicide by gas inhalation.

A hint, here, that Teena Mulder knows something... about something. Scully will discover that Teena was dying from "Paget's carcinoma," which, interestingly may be something of a misnomer, or a confusion of several possibilities. Mulder insists that his mother's undelivered message was about his sister, and that she was silenced by the Syndicate. And indeed, both agents have lost family to these particular murderers, and Teena had withheld crucial information before. Without getting too ahead of the game, let us say that Mrs. Mulder's message is never revealed, and Scully would seem to be correct. But why, then, does she burn the photo of her children?

Certainly she has left things unsaid, and if Mulder tends to categorize the Smoking Man as "a liar," Teena has a pattern of lying as well. The backstory unspoken in the "Closure" arc is that, at minimum, Teena was aware that Samantha's abduction was directly related to Bill Mulder's secret government work: in "Paper Clip", she revealed that Bill had asked her to choose which of the children would be taken, and she was unable to do so. As per "Talitha Cumi", she knew that an alien neck-stabbing weapon (a "plam," to those in the in-joke know) was secreted in a lamp in the family home. As she was stroke-striken at the time, and her son, bizarrely, never questioned her on the topic afterwards, none can say if she knew what the space-icepick was, or its purpose. The list of Things Teena Didn't Tell Fox goes on and on, but the extent to which she understood Syndicate/Colonist business is an unknown variable.

An appearance by Mom's ghost in Mulder's motel room gains no ground either. Mulder is unable to hear or see the apparition, but she appears to police psychic Harold Piller, and meanwhile her son gets a clue via automatic writing: "APRIL BASE." Given these events, all we arrive at are — surprise! — uncertainties and possibilities. The Scully Version is: "Mulder, she was trying to tell you to stop. To stop looking for your sister. She was just trying to take away your pain." Unspoken by both agents is the real possibility that Teena harbored a lifetime of regrets regarding her role in the fates of both her children — Fox's parentage, Samantha's abduction —, hence the burning of the family photo. What Mulder will ultimately conclude is that "I've been looking for my sister in the wrong place. That's what my mother was trying to tell me." This interpretation, predictably, has multiple potential meanings. Possibly Ghost Mom is pointing Mulder to April Base, communicating through the automatically-written note in ALL CAPS, as she once wrote PALM. Indeed, at the abandoned home where Samantha's hands are imprinted in the cement, and her voice is inscribed in a diary hidden in a cupboard, Mulder locates a necessary lead — specifically, that she ran away on the date the diary ended.

Another Truth is that Mulder doesn't find Samantha at April Air Force Base any more than he found her in the "Paper Clip" file. He already knows, or knows the possibility that she was raised in the Spender household. She told him this in "Redux", and if she was a clone or a hybrid or a not-Samantha of some kind, the handprints in the cement could still belong to that same clone. At the top of "Closure", Mulder combs through videotapes found at the Santa's North Pole Village theme park, where a serial killer Santa had buried the bodies of twenty-four children over forty years. Samantha is not depicted on the tapes, not found in the ground. Mulder confesses to Scully that "You don't know how badly I wanted her to be in one of those graves," as it would at least end the search. But Samantha couldn't be there. It would not make sense. Besides flying in the face of the Syndicate plot that the agents have agonizingly pieced together for seven years, Mulder would have some memory of a family trip to California. Should Mulder have found a cold body at North Pole Village, it would not be wrapped with a bow.

There are two poetical-cum-literal dimensions to the message from Mulder's mother that will unlock the business of "Closure". There are geographical coordinates provided, but as they lead only to information that is inconclusive unto itself (handprints, partial diaries, shaggy dog hospital reports), what the note really points to is a series of absences. A body, dead/alive or cloned would not be enough and Mulder has literally searched from the South Pole to North Pole Village, from exhumed graves to the astral plane, and Samantha is not Out There. He is looking in the wrong place.

Secondly, Teena's message is passed to Mulder through automatic writing. That is to say, of course, that it comes from himself.

Sky-Walker, Star-Killer

In real world New Age contexts, Walk-Ins are beings from elsewhere who have taken up in human hosts, replacing the previous consciousness. "Closure" calls its spirits "Walk-Ins," though this application of the term is unique to these episodes. A walking encyclopedia of the paranormal, Mulder would know what a traditional "Walk-In" is, and demonstrated such in the convoluted episode "Red Museum" (2.10). The creative staff is therefore making a choice to associate the "Closure" beings with run-of-the-mill Walk-Ins. So what is going on here?

The behavior and motives of the Walk-Ins are complicated and ultimately inexplicable. The cold open of "Sein Und Zeit" establishes the base pattern and "rules," such as they are, and kindly kook psychic Harold Piller names and explains near the beginning of "Closure"; this is the major loop of phenomenon and interpretation in the investigation of the actual X-File motivating the episodes. To the file cabinet, then.

Six-year-old-ish Amber Lynn LaPierre disappears from her bedroom in Sacramento while her parents are in the house. The name and circumstances echo aspects of the 1996 murder of JonBenét Ramsey, a crime already difficult to comprehend that in the ensuing decade increasingly resembled these no-answers riddles. Mulder horns in on the LaPierre investigation for its superficial links to Samantha's abduction, but besides a child missing with no trace, the incidents bear an important non-resemblance: no bright lights, no levitating girl, no family link to a government cover-up of an interplanetary invasion plot. Scully addresses the transparent psychology at work, and tells Mulder that if sympathy for missing children has drawn him to the LaPierres, he is also stretching to connect the apparently unrelated cases.

Amber Lynn's disappearance is accompanied by three unusual events. While tucking her in, Mr. LaPierre has a vision of his daughter as a corpse. Immediately before the girl goes missing, Mrs. LaPierre pens a ransom note addressed to herself and her husband, and making reference to Santa. Some time later, Mrs. LaPierre witnesses an apparition of Amber Lynn attempting to speak to her.

Recalling a similar confounding note in an apparently solved X-File, Mulder visits the jail cell of confessed murderess Kathy Lee Tencate. She does not quite say the words, but allows Mulder to conclude that given the confusing, inconclusive evidence (more automatic writing, another vision, another spirit visit), Tencate has made a false confession in hopes of appeasing the parole board. After some soul-searching and another visit from her ghost son, Tencate suggests to Mulder that Teena Mulder's message was that she, too, had seen the Walk-Ins.

Here, "Closure" enters that undefined space where metaphor and story events merge, swap out, and wear masks. It is remotely possible that Teena had visions of a dead Samantha, but when? Before Samantha disappeared from home? Years later, before she disappeared from the hospital? In the closing scenes, a retired emergency room nurse who was on duty the night Samantha was taken by Walk-Ins claims that she had the visions. A pile-up, again. The would-be Tencate and LaPierre murderer is given an inconsistent name by the episode closed captioning — "Ed Scruloff" in "Sein und Zeit" and "Ed Truelove" in "Closure" — which is indicative of this open-ended is/is-not pattern. While Scruloff/Truelove nabs victims from all over the country, their bodies are all buried at North Pole Village. The only two of his victims that are named are children he did not manage to kill at all, but likely intended to kill. Whether he ever left a ransom note (or why) is not established, nor is it clear if/how/why the Walk-Ins are leaving such notes. Just as Scully and Skinner indicate, Mulder gets so far off-track with the case's Samantha associations that he fails to notice that none of the evidence is adding up.

The role of psychic Harold Piller, who guides Mulder through "Closure" is partially expository, laying out the few rules of the Walk-Ins that he understands: the awful visions given to the parents are of the fates their children were about to suffer, and, the masterstroke, that "they will come to you if you're ready to see." But he is not there to circumvent the questions begged by the Walk-Ins, either as metaphor or physical event. When standing amidst the North Pole Village graves, Piller asks a question that plunges straight to the heart of the murk: "My God, why? Why must some suffer and not others?"

There is a lot of suffering to go around. As it happens, Scully discovers that Harold has previously been institutionalized, diagnosed as schizophrenic, and is under current investigation regarding his own missing son. These things are, of course, not damning, but they complicate things, they throw doubt, they open possibilities.

Though his own boy disappeared under identical circumstances, Harold does not see his double-exposure spirit, the final confirmation of Walk-In involvement and a tranquil death. But it is Harold's son that guides Mulder to Samantha's diary and escorts him to meet her spirit in the clearing at the end of a dark road. Mulder sees the boy only because he's "ready to see," which means as much and as little as that he Wants to Believe. Piller believes in the Walk-Ins in general, but cannot accept that his son is dead, will not listen to Mulder's advice that "we both have to let go." In his final scene, Harold runs off into the darkness on an endless snipe hunt. The road he takes is the one Mulder has been traveling since 1973.

The memory of Samantha leads Mulder to Amber Lynn leads to the Tencate case leads to the twenty-four children behind the Village lead to Harold's son leads back to Samantha. A series of infinitely nested X-Files, all bearing Fox's name, pasted over with Samantha's. Mulder is the Walk-In, here, the little girl is lost, but she lives on through her brother.

While Mulder is off chasing starlight still looking in the Wrong Place, Scully reviews arcane evidence from what will prove to be the Right Place. She watches videotape of Mulder's hypnotic regression sessions from 1989, where he first remembered the events of November 27, 1973. This is, in effect, where we came in. The memories unearthed in these sessions were the first intimate information that Mulder shared with Scully. It is the formation Fox Mulder, Investigator of the Paranormal. At the closing of the loop, the last evidence meets the very first evidence. The FBI psychologist reviewing the tape with Scully evaluates "this is just garden-variety compensatory abduction fantasy." This was always a possibility. The reason for a reminder at this point is to parallel the solution with the inception. In a rather audacious scene of the season 7 finale, "Requiem", an FBI accountant will ask: whether the Bureau believes it or not, if the whereabouts of Samantha are resolved, and the Syndicate is dismantled, what, exactly, is left to investigate?

The Walk-Ins may rescue some from painful injustices, but leave plenty of pain in their wake. The LaPierres will likely be convicted, Kathy Lee Tencate remains imprisoned, Harold Piller grieves forever, and billions of souls will not be rescued from earthly death. Why must some suffer and not others? In the final moments of "Closure", Mulder gazes at the stars once more. Faced with that field of graves, the lost child's empty bedroom, the sky of Infinite Samanthas, Mulder does what we all must do, and reconciles a mountain of ambiguity with an explanation that makes sense to him. His heart comes to rest on the stars, and not the blackness around them. He is finally looking in the right place.

- Chris Stangl at 10:25 PM 3 comments

Indexed in: television, The X-Files

Friday, October 29, 2010

Backwards, Forwards, Now to Then: Happy Birthday, Winona!

A birthday well-wish on this ought-to-be-a-national-holiday, to Ms. Winona Ryder. Her twenty-four years of on-screen work, beginning in 1986, have all been interesting (and yes, a subject of this journal's unbending fascination), and in her thirty-ninth year on Earth, she enters a particularly promising phase in career terms, participating in Black Swan for Darren Aronofsky (ergh/yay) and a Frankenweenie remake (wha?/yay) for Tim Burton. Ryder's natural place in the cinemasphere is in contentious, off-beam projects by filmmakers strong of vision and colorful of personality. Because it is nice for work one enjoys to be seen and discussed, let us hope these films catch on in ways that recent endeavors like A Scanner Darkly, The Ten, Sex and Death 101 and The Informers did not. But if not, no sweat, for Ryder's performances enrich those very entertaining curiosities, and relative stardom is not a measure of artistic success. At any rate, the actress appeared rested, healthy and glowing at recent premieres for Swan, and that is happy news enough.

The image above comes courtesy of 1999's Girl, Interrupted, of course, some three minutes into the picture as Susanna Kaysen (Ryder) undergoes psychiatric interview with Dr. Crumble (an unctuous Kurtwood Smith, doing a caring, patronizing variant on his timeless signature sentiment "Bitches, leave!") following an Incident involving a bottle of asprin and a bottle of vodka. Susanna is decked out in natty nautical stripes, a sort of cartoon convict uniform that echoes her looming imprisonment at Claymoore Hospital. Nerves bundled, she tries to maintain the keel of the conversation, but Ryder shakes her voice on selected notes and makes clear how hard it is to stay above water. She's playing it on Levels, attempting to plainly explain her mental experience while aware of how she's being interpreted and the consequences of each word, and thus takes it slow, pained and honest. She spends most of the scene looking through the doctor, probably appearing spaced out, but really spaced too far in.

Explain what happened? Moving into close up, Ryder doesn't exhale her smoke, but lets it puff out of her mouth and nose as she speaks, an uncontrollable cloud that pops out in embarrassed spurts that she cannot contain: "Explain to a doctor that the laws of physics can be suspended? That what goes up may not come down? Explain that time can move backwards and forwards and now to then and back again and you can't control it?"

And here a dog barks, further distracting Susanna, as the doctor asks "Why can't you control it?" Ryder winces hard trying to make sense of the question, determine if she's reading too much into it, and to be heard over an internal din that is bothering only her, asks a little too loud: "What?"

Dr. C: "Why can't you control time?"

And to that, a patented Winona Ryder look: aghast, disgusted, and terrified at once. How about it, lady, why can't you control time? — not a bad sentiment for birthday times, that. A beat, one blink, and she breaks the brief eye contact.

The scene also has probably the best possible answer to the age-old question "Are you stoned?" (that is: blank stare). As the only sort of birthday present I am qualified to offer, I celebrate this Winona Ryder screen moment, and add it to the collection of randomized masthead images at the top of this page. So to The Exploding Kinetoscope's favorite actress, happy birthday again, and hey, don't worry too much about that controlling time thing.

- Chris Stangl at 6:24 PM 0 comments

Indexed in: birthdays, Winona Ryder

Monday, October 18, 2010

Hey Look, It's Ringo and Frankie!

Under consideration, this universally beloved shot from Stagecoach, the one that moves from this:

First things first and sliding immediately off topic, there are plenty of images capturing this moment all over the Internet and I might have swiped them for illustration. Unless making a point with incongruous stolen pictures, I try to create my own screencaps whenever possible, because, like Quaker Oatmeal and recycling beer bottles, it's the Right Thing to Do, and because there's a certain art to screencapping, one for which I sorta like to think I have a flair. David Bordwell would surely have a lecture for me about the inadequacies of the practice, but it's all I got. In this case, an even worse sin, I can't make frame enlargements and can't take frame grabs of Blu-ray discs. For all Blu-ray's myriad pleasures (including the fun of typing the gimmicky e-less "Blu"), the inability to screencap is an ever-increasing hindrance to the important work we do here. Sadly, the only other option is to, uh, take pictures of my TV screen, which is a hideous solution, and photography is an art for which I do not have a flair.

Anywhich, back to the shot in question. It is the first shot of John Wayne as the Ringo Kid, a gasping, audacious hero shot that stops the stagecoach in its tracks, dollying up on Ringo as he twirls his rifle, yells "HOLD IT!" and has a sudden, barely perceptible change of expression. Wayne has struck an elegant pose even though he's toting a rifle in one hand and a saddle in the other, the strain of this ridiculous feat betrayed not by his casual posture but the sweat streaks on his face that aren't apparent until the shot moves in. Basically it is an unforgettable, electric-buzzed moment and every element is perfect, even those that are not. Specifically, 1) the movement is just slightly faster than expected or is comfortable, and 2) this famously causes the shot to pop out of focus as it repositions into 3) the whoa-just-slightly-too-close close up of Ringo. There is a vast amount Stuff Going On in this shot which does not last more than three seconds, from the aureola crowning Ringo to its importance in Wayne's career, but I don't think it is fully unpackable because part of its power is of disruption; the thrill is in the way it feels subtly off, arhythmic and just-out-of-control.

That said, it is cemented into the film and a piece of a scene, and some of this impact comes from 1) the whinnying horses immediately before the shot. The eye-catching movement in the preceding shot is the horses pulling back in reaction, effect being that the dolly-in is pushing off of the backward momentum of the horses.

2) a goofy two-shot reaction of Curley (George Bancroft) and Buck (Andy Devine), immediately after, where Devine chirps "Hey look, it's Ringo!" in that inimitable Andy Devine way. On the front end, the picture-story is that the stagecoach crosses a ford in the river and comes toward camera, the effect being that the coach is pulling up on Ringo and drives straight into a huge view of his face.

So it's all in reaction and juxtaposition, and I'm going to say that Andy Devine is quite responsible for making this one of cinema's greatest entrances.

Speaking of which, we all have our favorites, and my shortlist would include Peter Cushing in Frankenstein Must be Destroyed!, Johnny Depp in Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest — elaborate setpieces climaxing with thrilling reveals and introductions that we won't go into right now, but top Orson Welles in The Third Man — keep some popular favorites (Karloff in Frankenstein) and dump others (Darth Vader in that movie about Darth Vader). This scene in Stagecoach, however, always puts me in mind of another great movie entrance, Tim Curry as Frank-N-Furter in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (yes, yes, he is visible as another character earlier in the film).

The reason the entrances of the cowboy and the transvestite alien reverberate off one another — though come to think of it both are fugitives from justice, questing for freedom and non-judgmental of the sexuality of others — is simply a jarring push in from this:

But of course, while prepping these screencaps, it became clear that the moments are very different. The effect as a memorable, keyed-up introduction to a character is similar but John Ford does it with effortless 3-second economy, while RHPS director Jim Sharman is simply up to something else. Ringo appears during a lull when we aren't really expecting it, while Frank-N-Furter's entrance is a mini-climax to which a whole sequence is building. The first close up of Frank is, indeed, a privileged shot, but it is punctuation on a scene.

Frank's entrance in Picture Show has been moved from its place in the stage musical The Rocky Horror Show. In plot terms, this merely swaps the positions of the numbers "Sweet Transvestite" (first in original stage productions) and "The Time Warp" (first in the film). The reasons, one supposes, are that "Time Warp" is the sort of "hit single" of the musical, a live showstopper to which the play builds up, in a loose-knit plot that is an excuse for the songs. The film is more dramatically developed, and thanks to lessons learned from the stage show, has a better grip on pace and payoff. Once Tim Curry appears, the beast is basically loosed and one wants to get on up to the lab and see what's on the slab, rather than dally downstairs for, as Brad Majors puts it, "more folk dancing."

The scene bridging the two numbers then is not just an introduction. By repositioning "Time Warp", there is a gap left where there used to be an exchange concerning the whereabouts of delivery boy Eddie. In place of this missing exposition, the film adds: nothing. That is, the film's transition adds no additional narrative information, but creates a musical bridge, uniting a pair of songs. Frank descends to the first floor in an elevator behind Brad and Janet, and this little scene is scored with sound effects (and percussion) that build off the discordant piano banging at the end of "Time Warp" and ramp up to the fanfare at the top of "Sweet Transvestite". The instruments in play are a base tone laid down by the lowering elevator, a chorus of the chortling Transylvanians, the rhythm section stomp of Frank's platform heel, and the mounting chant of Brad and Janet's dialogue in metered back-and-forth ("I'm COLD, I'm WET and I'm just plain SCARED!"). This audio piece terminates with Janet screaming as the zoom into Frank's close up comes to rest.

The above awkward screencap of Brad and Janet in front of the elevator comes straight off the top of the shot in question, after Janet has already noticed the figure in the cage. The sort of platonic ideal of the composition is in a pair of earlier shots, like so:

Besides the aural component, the gag being staged in this scene is that the square couple is backing out of the ballroom, away from the Transylvanian weirdoes but into Frank in the foyer. So there are cutaways for reactions (Transylvanians rising from the floor as they see the elevator descending, Transylvanians assembling around red carpet, Janet goggling at Frank's back) and clarifying information (two close ups of the stomping shoe), all building anticipation for the reveal of Frank.

The screenplay's newly invented bit of business is well-motivated, with Brad dismissing Janet's rising hysteria by condescending and trying to minimize her concerns (Frank will later diagnose Brad: "Such a perfect specimen of manhood. So dominant."), and the rousing of the "Time Warp" spent Transylvanians providing reason for the couple to keep their eyes on the ballroom. Immediately after the money shot, before the gate slides open and "Sweet Transvestite" proper begins, Curry's close up is disrupted by a reaction shot of Janet, who becomes over-stimulated and, in running gag, faints. This puts a button on the scene, separates the elevator shoe-stomp as its own mini-song (audience participators traditionally stomp and clap along), and Janet's response cues the audience on how to react to Frank-N-Furter — that is, somewhere between Beatlemania-style abandon and what-the-fuck gaping. In short, Susan Sarandon provides the Andy Devine effect here.

- Chris Stangl at 9:46 PM 0 comments

Indexed in: John Ford, music, Rocky Horror Picture Show, Western

Monday, October 11, 2010

Scare-stounding DVD Covers!

Gee, it's been awhile since... YOU SAW SOME ASTOUNDING DVD COVERS.

No, really guys, I'm, like, working on stuff!

In the meantime, kick back with a bowl of Brach's Autumn Mix and look at these Astounding Ones of October. Or should I say... SKELETON-TOBER?!

- Chris Stangl at 10:29 PM 4 comments

Indexed in: astounding DVD covers

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Freleng Studies — The Deadly Numbers of SATAN'S WAITIN'

"Satan's Waitin'" (1954) is a cartoon about death and is structured a bit like a classic Ten Little, Er, Indians style pick 'em off, of, if you prefer, a Bay of Blood style slasher picture. The twist is that we're watching the same victim bite it in colorful ways over and over, as Sylvester runs through his proverbial nine lives in seven minutes. The slasher in this case is the Devil in the form of a crimson bulldog, which is a metaphor for Sylvester's worst, obsessive, Tweety-hunting impulses, natch.

So here we have a couple of Freleng's own fixations on display, i.e. the neuroses and psychological torture of Sylvester (Tweety is barely in the cartoon except to motive the story and provide an ass joke when his tail feathers are yanked) and a certain philosophical morbidity that crept into his '50s shorts that is perhaps noirish or Hitchcockian or about the comic possibilities of Order and Chaos pressing and pulling at the weak soul of the cartoon animal Everyman. Whatever the conclusion I note a vague sense of postwar malaise in Freleng's work of this era, if not one totally distinct from other brands of malaise. This isn't a truism across the board, but when the quality is there, it is there in force, and not to be found with his peers. There is a terrible geometric order to "Satan's Waitin", to graphical wit, the pussycat and the canary on precarious chase across a sky carved by intersecting phone lines:

The most restrained, buttoned-down of Warner's major cartoon directors, Freleng's world is not populated with the flailing, screaming humanity of Bob Clampett's, his characters do not explore the complex, broad swath of human personality as Chuck Jones', his stories do not balloon out to the extreme proportions of Tex Avery's. And etc., not to tromp over a well-worn favorite stomping field of animation pundits; point is, speaking of formal issues of character animation, Freleng's cartoons don't squash as much, don't stretch as much, they don't antic as big, don't do takes that distort anatomical forms into graphical abstractions. Now all of this is of variable Trueness, depending on the staff for a particular short and who was actually animating a particular sequence, but certainly Freleng did not ask his animators to hit bigger, crazier poses, infuse acting with more personality and presence, or pick up the pace for the joy of speed. And on one hand, that is not as funny, and perhaps Freleng is puzzlingly lacking that cartoonist's gene that loves a funny drawing. On a different, more contemplative hand, stillness, stiffness, intellectual detachment and a cool demeanor can, indeed, provide a much different sort of comedy, on the Charles Schulz, Chris Ware sort of end of the comic spectrum.

Why was Freleng obsessed with Sylvester? It's not Tweety that the director is interested in — he defanged Clampett's sadistic-widdle-kid character and in design, function and performance drained the bird of a distinct personality rooted in human traits. Certainly every other director artist drew a funnier Sylvester, where Freleng pulled back on the character's previous stupidity and thuggishness. In place of the older Sylveter, here is one sweat-drenched and helpless in the face of his own compulsion.

Anyway, "Satan's Waitin'" is a study of graphic contrasts, spatial orientation, shapes and visual rhymes, and above, the hunter and prey locked in cycle scramble up a fire escape. The only reason to head to the rooftops in a cartoon like this is because someone is going down, and as it happens, Sylvester's journey up the fire escape ends in a pit of flame.

The abyss awaits! Hover. Hold. Beat. One of you is getting out of this alive.

So there's a cause/effect elegance to the cartoon's up/down see-sawing, doubled here as Sylvester's tail is his last erect extremity, then the tail flops down, then his soul springs up out of his butt in its place. A pair of brick and sidewalk square grids reinforce the visual order, but chaotic cracks in the cement emerge from under the cat's corpse, hinting at something else.

There is no tally provided of Sylvester's sins. He has simply Been a Bad Pussycat, and must take the red escalator every time, no matter, as we will eventually see, how he tries or what he does. The vagaries of moral rectitude flit around the fringes of "Satan's Waitin'", and the cat's only crime seems to be the attempted fulfillment of his natural predatory instinct, not that acting on instinct ever got anyone on the golden escalator. Though plenty of cartoons want to get in gags with wings and halos, I would naturally assume that all Looney Tunes characters are going to Hell.

Background painting people, do glance at the complimentary red and green buildings splitting the space between escalators.

Yawning chasm, fanged rock formations, spiraling conveyer belt to damnation.

The story here is that Sylvester's numbered lives must tarry in Hell's waiting room until all nine of their fellows have arrived. The structure is a countdown as the cat loses lives during the course of one long chase scene, with pit stops for exposition.

Life #2 arrives after a tangle with a steamroller. Again, scrambling life-drives are pinned and pressed into two dimensions and squeezed straight through the ceiling of Hell.

"Scare Your Girl," indeed. There are a handful of fine signage gags in this cartoon, another Freleng trademark, if not an exclusive one. Dig also this abandoned urban space, in the middle of an unpopulated city stands an empty carnival about to become a literal carnival of souls, lending an amplified quietude and desolation. There are production, budgetary and technical reasons for the minimal cast and lack of extras in animation, of course, and changing tastes in art and design have a lot to do with the modernist look of '50s and '60s WB cartoons. On the latter front, however, Freleng and Jones were usually ahead of the curve.

More nice muted primaries here; look how this says "carnival" and is all red, green and yellow but isn't just an out-of-tube eyeball cacophony. There's also a clue in the middle to a motif of Sylvester's being plagued by demons, and a big yellow paw that will pay off in a few scenes.

Nice dynamic staging. Noir-y, Third Many shadows that also popped up on Sylvester's first descent to Hell. There is a lot of movement along the z-axis in this cartoon.

Satan is everywhere.

Point demonstrated, I hope, about Freleng's comic reaction takes. Even the moment where Sylvester is so terrified that he dies is not much bigger than this.

Sylvester loses lives four through seven in rapid order on this shooting range. Though it is not different from any other cartoon shooting range, because of its place in this farce of certain destruction, this one seems a particularly apt, fatalistic metaphor: lined up, on track, ready to be blown apart. Also, more signage, more vague, useless moral instruction: "Shoot straight." Yes, good luck with that.

So, the way Freleng stages the gag here is to cut back to Satan's waiting room, as we hear gunfire, victory bells, and bang bang bang bang, dead cats are deposited in a row. There was probably a moment early in the film when we expected nine cat mangling vignettes. Confounding expectation, Freleng burns off four of Sylvester's lives in seconds.

Here begins the speediest sequence in the cartoon, and speaking of movement from back to fore, this roller coaster train slowly climbs the distant hill before rocketing downward — which is rather how we began this story. Then it charges at the viewer's damn face, which is a good deal more alarming than Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat, and then zooms over the screen. What's happening here, and in another directly-overhead shot of the train charging down a drop that I haven't pictured, is a) complicated staging with difficult angles, beautifully animated with mathematical precision...

b) more open space netted by intersecting lines, c) the visual rhyme and gag setup that is the reason the escalator to Hell was designed as a long, red, twisty track.

Point A above kind of makes up for the subdued character animation and mild gags. No doubt any other unit was up to the task of pulling off the scene, and if, say, it had been a Clampett, the scene would likely have the visceral impact of riding a roller coaster. Jones would have blessed it with his — how do put it? — peculiarly sardonic sense of physics, and both others would have done it all faster. But faster, gutsier and (ahem, funnier) bloodier is not the point, the point is the go-nowhere trip along a one-way track.

Relish the spare, allegorical quality of this particular pose, and the clever, don't-blink touch of marking the car #9. Because it's the little things.

I note for anyone without art inclinations that drawing this angle totally sucks.

This is the important part of this shot. Were this a Jones Roadrunner cartoon, the timing, the drawing, the sound effect would make the moment of impact the joke, maybe with a microbeat of I-fucked-up Coyote recognition before the carnage. Here it is the belated behavioral instruction that is impossible to follow, and doom rushing at one's head.

Payoff. Probably the funniest cut in the cartoon is between the coaster massacre and the above match, Life #8 blank-eyed, silent, no reason to fight this anymore.

Meanwhile, topside, Sylv takes the "Time Enough at Last" approach and seals himself up in a bank vault. Not trusting his unrestrainable urges, and trying to minimize the universe's chaotic x-factor input, he goes on defense. We'll note yet again that this designy vault is all grids, quads and circles, and fair enough, Everything is Shapes, but '50s design only emphasizes this fact (and my roundabout point is that the cartoon is kind of in dialog with that idea).

Naturally, Satan being Everywhere, two bungling robbers try to dynamite open the vault and kill everyone in the process. And on that front:

-The last manifestation of "Satan's Waitin'"'s thematic/visual theme of agents of explosive chaos and confining order sort of luring then breeching one another. Also crime does not pay, but neither does not doing crimes.

-A mild send-up of atomic age bomb shelter mentality.

-Another cut-to-result staging of a violence gag. Freleng doesn't show the explosive, the explosion or the corpses, just:

- Chris Stangl at 2:55 AM 2 comments

Indexed in: animation

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

Weekly Deprogramming Schedule — #3

Masters of Horror: John McNaughton — "Haeckel's Tale" (2006, John McNaughton)

Originally earmarked for direction by Roger Corman, passed at some point to George Romero, the MoH first season finale ended up in the hands of John McNaughton. While I greatly enjoy the maniacal Wild Things, no disrespect intended, but McNaughton is not Corman or Romero. When "Haeckel's Tale" was broadcast it had been twenty years since McNaughton directed his only nominal horror film, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. This is my sneaky way of suggesting that some of the "Masters" of Horror are not masters, or maybe not even specialists in horror, which may account for the general lack of mastery on display. This is my kind way of saying that this promising premise resulted in a generally junky program.

Point in case, "Haeckel's Tale" is based on Clive Barker material, which ought to prime an audience for hideous transgressive visions, bizarre plot inventions or at least some weird gross-out shit. What transpires is an absurdly padded out buildup to a laugh-riot punchline that maybe is/probably isn't supposed to be funny, which is that a 19th century country lady has a sex orgy with zombies. Everything is wrong here: go-nowhere reference to historical figure Ernst Haeckel, telegraphed twists, pointless sidetracks exploring God's Domain vs. science vs. Frankensteins vs. necromancy, circular conversations repeated over and over, and poor Jon Polito wearing a long gray wig. The self-negating frame story, for instance, sees an old lady telling a cautionary tale about why not to raise the dead, when the twist reveals that she gets it on with revenants all the time. In one of those special moments where nails are struck squarely on the head, a zombie dog pops out of a trunk and wriggles around in sub-par special effect fashion but our skeptical protagonist scoffs "it's some kind of crude puppetry!"

On a more important note, "Haeckel's Tale" was scored by avant-garde music heroes The Residents, whose work was then rejected and replaced. This previously unreleased material is currently available for a pittance at the group's newly mounted download store. As the Rez say, Buy or Die!

Masters of Horror: Tobe Hooper — "The Damned Thing" (2006, Tobe Hooper)

What this amiable mess seems to have borrowed from Ambrose Bierce is a title and the image of a man killed by an invisible creature. Basically the deal here is that an unseen horror of some kind stalks Cloverdale, Texas, but is mainly after poor Sheriff Reddle, whose family was wiped out in an attack 25 years prior. "The Damned Thing" tries out and swipes a dozen different ideas, and may be amusing or effective in the moment but the whole thing just doesn't track. It's got a small community devolving into a mob of crazies (like The Crazies, sure, or "The Monsters are Due on Maple Street"), a small town in denial until its sins come to roost in supernatural form (like Stephen King in It, 'Salem's Lot, Cujo, etc.-forever mode), nuclear family meltdown as psycho dads hunt the wife and kids (an extended Shining swipe), a horror passed through generations of the same family (like, er, Jaws the Revenge, maybe), and a sub-Smog Monster not-quite-environmental-parable about tampering with the mysteries of nature (SPOILER it's a giant oil monster that wants to eat the Reddle family because they built an oil rig). Sometimes the monster is invisible, sometimes not, sometimes its presence drives people to aggressive violence, sometimes not, and the story sorta makes sense but really does not.

As an addition to the Hooper legacy "The Damned Thing" is obviously minor work, less ambitious but less botched than "Dance of the Dead", and not as much fun as The Mangler. The episode's most effective sequence in terms of plain, wincing horror and oh-goddamn! surprise is of a man attacking himself in the face with a claw hammer. Clearly this Tobe Hooper has a talent for horror about the misuse of hand-held woodworking tools, and that skill ought to be channelled into something of more consequence than "The Damned Thing".

The Garbage Pail Kids Movie (1987, Rod Amateau)

Every time one sits through this treasure trove of appalling images, something new will bother the edges of the mind and haunt the viewer well into slumber. Perhaps it will be gutter punk fashionista Tangerine spreading her pantyhose'd crotch in order to entice 14-year-old Dodger into allowing her to exploit his home-sewn garments (don't worry, she's fifteen, herself... or maybe do worry). Perhaps it will be the never-again-referenced title sequence that may or may not imply the Garbage Pail Kids are extraterrestrial beings. If you haven't seen The GPK Movie — or, rather, Experienced it —, it is the dingiest-looking, most unpleasant children's movie ever made and is about how the a bunch of toddling dwarfs in walleyed rubber baby masks puke, snot, fart and piss all over and help a little boy try to score with a gang leader's girlfriend by using their magical sewing skills.

Like I said, something new every time. This go-round it was a little girl sneering "Go suck a rope!" at the men from the State Home for the Ugly who have caught her in a butterfly net. The image of the pummeled Dodger doused with raw sewage by bullies is enhanced when one remembers he is covered with open wounds. A newly discovered puzzling detail: a painting from fellow fucked-up family classic Troll (1986) is prominently featured on the stairs to the antique shop basement where the GPKs are held captive. The overlapping staff between productions does not seem to include the art directors or property masters, but the films do share the same special effects crew and Charles Band's favorite thespian, Mr. Phil Fondacaro. Perhaps the Troll painting resides in the Fondacaro archives, or maybe like the Garbage Pail Kids driving off into the night on ATVs, some mysteries are like the wind.

Credit also to the lady of the house for noticing that among the cluttered set dressing a nude Cabbage Patch doll hanging by its neck in a rusty bird cage.

The Informers (2009, Gregor Jordan)

The Informers is set:

a) in Los Angeles, 1983.

b) in a world of people who can afford to sit around watching MTV on Eames furniture in their underwear, with some sidetracks to a fanciful vision of how not-rich people live (selling abducted children to rich people).

c) deep inside Bret Easton Ellis' stalled-out brain.

d) who cares? It's over. It doesn't matter. Like... it doesn't matter.

The fourth screen adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis is apparently the writer's least favorite — he's even gotten soft on Less Than Zero — because it "doesn't work," as he told Movieline and more helpfully lodged the complaint that "it’s not supposed to be played like an Australian soap opera" and that his own vision for the project was funnier. Not being versed in Australian soap opera, I can only say that the tone is perfectly appropriate for an Ellis adaptation, that being suitably zoned out portraits of wastoids punctuated by hysterical potboiler speeches, fights and meltdowns, and shrill moralizing throughout. To be fair, Ellis can sometimes be actually funny — my favorite moments are Patrick Bateman hallucinating a television interview with a Cheerio in American Psycho, and a possessed Furby emerging from a dog's butt in the bonkers Lunar Park. He usually settles for Warholian jokes funnier to talk about than to experience, such as endless lists of characters' designer consumables, celebrity names, sex acts and drugs.

All four Ellis adaptations offer valid, committed takes on the material, all emphasize and capture different aspects, but all are sincerely Ellis-ian. The Informers specifically nails Ellis' cold, sheeny prose, affectless characters, leaden, portentous symbolism in every prop, backdrop and air-sucking line of choked dialogue. Gregor Jordan's film is mostly shot in that too-bright gray of overcast L.A. and his chilly liquid camera moves like it's been resting in an ice bath. Lots of shots of people staring off and thinking/not thinking.

The Informers retains the book's interconnected short story structure but cuts between story threads, in the tapestry narrative tradition of Nashville and Short Cuts, rather than the anthology tradition of Fantasia or Dr. Terror's House of Horrors. Also unlike any of those movies, the hoard of characters are all creepy disaffected idiots and nothing particularly happens in any of their stories. For example the rock singer for the titular band, The Informers, sits around a hotel, ingests substances, cuts his hand, sexes underage groupies, doesn't sign a movie deal, makes a phone call and finally punches a groupie. While magnolia is built of a dozen small stories packed with incident, intricate overlap and convergence, and Crash (2004) has a certain thematic unity and its interwoven sprawl is part of its purpose, The Informers is glued together with persistent drone, its characters largely linked because everyone is passing around the HIV virus, and its theme that everyone is an amoral shitbag trapped in stasis. I'm gonna go ahead and say I think it is surprising and questionable that a gay man who lived through the era would write a satire about the early '80s in which one of the blackly comic jokes is that the whole cast is spreading AIDS to each other, then complain that he wanted the movie to be more "light-hearted." Or it would be surprising if the same guy hadn't written a book with a severed head on a boner, then complained that critics missed the satire.

The magnetic cast gives all kinds of alienated, glassy-eyed and ridiculous, and there are some killer scenes built around very fun performances. Mickey Rourke abducts a child in broad daylight by scooping the boy up and chucking him in a van, and it looks like documentary footage of what Mickey Rourke happened to be doing on his way to set. Billy Bob Thornton as a sociopathic movie studio head corners his mistress, Winona Ryder, in the Spago ladies room. She keeps trying to break up with him and he just smiles calmly and doesn't listen, and she bugs her eyes out, sputters and just can't fuckin' believe his gall. Another diverting Ryder scene sees the nicotine-fitting news anchor harassed by a sniggering rock band during lunch at Canter's deli; it's a sharp and specific confrontation as privileged L.A. square culture and snotty hipsterdom look each other up and down. Stealing the whole mess is Chris Isaak, looking very much like Kurt Russell and playing a terminally dorky dad trying to bond with his bratty, resentful son on a Hawaiian vacation. Again, nothing really happens in any of these stories and that's sort of the point, so in a way these amusing performances are working against the spirit of the material.

If you have read the novel, be warned that all the vampire parts have been removed which makes the film less silly and entertaining. If you have not read the novel, unlike the movie, it has vampires in it, which makes the book stupider but less vague about why kidnapping victims are being sold to Hollywood creepos. Jury is out on whether it is weirder to adapt a vampire book and cut out the vampires, or that vampires could be inserted or removed from a story with no appreciable damage.