Getting Drunk With SPIDER-MAN 3

SPIDER-MAN 3 (2007): What? Are you just going to sit there glowering all night?

CHRIS STANGL: Hm.

SM 3: Fine, have it your way.

CS: How much did it cost to make one of those CGI cinder-blocks that MJ uses to smack Venom in the climax?

SM 3: Low blow. You're buying me drinks just to insult me?

CS: I already dropped $20 on a ticket, Junior Mints and a coffee just to be insulted, Mr. Most Expensive Movie Ever!!!, and now I want to know how much one of those cinder blocks cost.

SM 3: Come on...

CS: Okay, okay, it is unfortunate that David Lynch has to distribute his own movies, while Sony will spend $300 million dollars on a ticky-tacky second-hand super-schlock; but honestly, I'm not suffering under the illusion that money would go to better use anyway. It's a cheap shot, and I sort of kind of apologize, or can overlook that. But whether any film should cost so much, on a pragmatic level, I admit, I'm not sure I care.

SM 3: If you're playing fair, then, I'll buy the next round.

CS: I'm already relegating Spider-Man 3 to novelty gimmick-review and putting words in its mouth, so this one's on me. Garçon? Mai tai for me, cheap domestic brew for the lady.

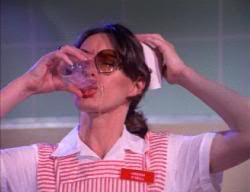

BRUCE CAMPBELL AS A FRENCH WAITER: Oui!

SM 3: You don't have anything nice to say?

CS: Bryce Dallas Howard is pretty.

SM 3: That's it?

CS: She's... really really pretty?

SM 3: So you're happy?

CS: No, she's in the movie for five minutes. Face it, Tiger, you hit the jackpot on Howard, and then blew it.

SM 3: I'll bite, what's the matter?

CS: Gwen Stacy's the matter.

SM 3: Oh Jesus, you care about Marvel continuity now? Since when? I s'pose you're in a tizzy that Reed Richards didn't help Spidey out of that black suit.

CS: If it was going to be the movie Reed Richards, no, I'll take a pass on that one. No, I care about giving five minutes of screen time to Bryce Dallas Howard, when she could've been the female lead of an entire film. I care about giving the best actors in the film - and that's Howard, James Cromwell, Theresa Russell - nothing to do. And you know what? This is always a problem with adaptation. The defense of lazy screenwriters can no longer be that the film is its own entity and owes no tithe to the story that birthed it.

SM 3: A movie can't compress, and I'm sure anyone would agree, should not compress forty years of monthly comic continuity into a two hour story - or over three two-hour stories.

CS: I was kind of hoping you’d say that. Spider-Man 3, like most of the contemporary crop of superhero movies, treats the material it's adapting like crab legs, cracking the mythos apart to get at the Good Stuff. It may be a logical start, but when the structure has been shattered like that, it needs to be reconfigured to function as its own Erector set contraption. If you can’t fix it, there’s no excuse for breaking it.

SM 3: So what’s the complaint? Please tell me it’s not “too many villains.”

CS: Absolutely not. It's not an inherent problem for a story to have three baddies. It's just tricky and requires nimble, focused storytelling. The Marvel Universe is a teaming place, and it should feel like one, after all. No movie has captured that but the Destroy All Mutants! attack at the climax of the turgid and frustrating X-Men: The Last Stand (2006).

SM 3: Because everybody says Batman and Robin (1997) had too many villains.

CS: Batman and Robin has fewer villains than the infinitely more sprightly and pleasurable 1966 Batman movie, and no more than the mentally unstable Batman Returns (1994), no more, really, than killjoy Batman Begins (2005). Regardless of what one thinks of those pictures, there are four closely related stories, all with distinct approaches to Super Villain value-packing. Spidey 3 never finds an elegant way to introduce, integrate and dovetail the stories of all Peter Parker's new adversaries.

SM 3: Three counterpoints to this line of questioning, then. Arguably, the constructions of all those Batman movies are unsound, so are there triple-threat stories that work?

CS: Just last year, there were at least three diverse villains plus associated cronies and sea-monsters to worry the heroes of Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest, and it tells a spry, constantly inventive story in which those villains have dimension, their stories ultimately converging and driving one another. It's not a physical impossibility, but if it is such a struggle as Spider-Man 3, better not attempted at all.

SM 3: Secondly: the Sam Raimi Spider-Man franchise maintains far more fidelity to the source material than the Batman TV-show, or arguably any large-scale superhero adaptation ever. Why not cut some slack here?

CS: It's because Spider-Man 3 is the Most Expensive Move Ever Made that it should be held to high standards, and that it should have to answer for itself. It's because it tries to maintain, reference or swipe so much comics continuity which is both beloved and successful storytelling, that the rationale behind that choice and the degree of success to which it bears that out should be questioned. Attention and care should have been lavished on this project -- all three of these projects -- and were not.

SM 3: Thirdly, we need more booze.

CS: And on that, I concur.

SM 3: You're talking like comics continuity is holy writ. It's a stiff, unpliable and unfeasible way to attempt adaptation from a print medium.

CS: I realize it sounds that way. And when it comes to Harry Potter, or the upcoming Golden Compass movie, I admit: in that case I may be blinded by love for those books, and have difficulty accepting alterations from the source material as a matter of course. But I just want a story that works. This is a movie that has Dr. Curt Conners, cast with a character actor with no hope of becoming the Lizard simply because he's not an A-Lister, flatly declaring "I'm a physicist, not a biologist." If your idea of how to tell a Gwen Stacy story is to use her as a pawn in the Parker/Watson relationship, then you care about that character far less than a CGI cinder block.

SM 3: Gwen is a far less interesting person than MJ, and she's only there to die and make Peter sad.

CS: First point yes, second point: Gwen is Peter Parker's One True, and I'm not taking rebuttals.

SM 3: ...and that's why it's been that Watson girl all along, in the movies.

CS: Gotcha!: then why introduce Gwen at all, after you've killed Green Goblin? If your series is supposed to get more mature and complex (buzzword for this is, apparently, "darker") as it progresses, why not at least bring Spider-Man Chapter I to a dramatic crisis with Norman Osborn killing Gwen? Plus you can spin off your bullshit Punisher movie off the franchise.

SM 3: C'mon, man.

CS: Kidding! There's simply no need to drive a wedge between Peter and MJ. That's what the second movie was supposedly about. Speaking of nonsense stories, you wanna explain why Spidey loses his powers in Spider-Man 2?

SM 3: He stops believing in himself!

CS: Sorry, I musta missed that origin story where Peter Parker was bitten by a spider that really really believed in itself. This is the kind of sloppy story logic, disguised as "character-oriented" that plagues the Spider-Man movies. The script needs to pay off Harry Osborn's feud with Peter, the dramatic conflict at the heart of this trilogy. For all James Franco's protracted three-movie brooding, Spider-Man 3 seems to think it requires further exploration of why a maladjusted man might want to avenge his father's death. Witness as he hatches his ultimate revenge, a diabolical scheme to... break up a teenage couple who is having problems anyway! The movie seems to have its hands too full because the overstuffed plot-sausages never collapse into one edible string of links. Peter has, in the grand Marvel "superhero with problems" tradition, plenty of potentially meaty stuff to deal with, all of it botched. He's getting a swelled head over Spider-Man's loving public, the ace-in-sleeve for this plot, but where pride should go before the fall, here it's simply unresolved. Mary Jane's petty jealousy is supposed to be a character arc of some kind, but Pete's oblivious to this. His secret identity's job security evaporates with the arrival of Topher Grace as Eddie Brock, Jr, (here a Photoshop-happy photographer)... but this rival simply acts like an equally doofy tool, just an amoral doofy tool. Brock gets to smooch on Gwen, and gets riled by dark-Parker swiping his girl, but it's not like this is a more compelling sore-spot than having been caught in bad journalism habits by Spider-Man, as in the comics. 'Cause factoring in Harry pursuing Mary Jane by frying an omelet with her in a scene from '80s Cringy Romantic Comedy Bullshit Montage: The Movie, it's not so much a love-triangle, but a half-baked love-pentagram.

SM 3: Soap-operatics are the Marvel hallmark, and you know it. Also he's upset about avenging his uncle's death.

CS: Wait, are we talking about the first movie? Because that's the story of the first movie.

SM 3: No, it's also in Spider-Man 3.

CS 3: It certainly is. This isn't dramatic arc, it's a closed worry-path, a movie pacing in circles. Tobey Maguire has to shoulder the worst of these sins. He could be a fine Saturday matinee Peter Parker, lovable bug eyes, overbite and lisp playing push-pull with the limits of good-looking and total nerd. The character is a put-upon human being first, and a hero second; that's the masterstroke concept, and Sam Raimi gets that. The plot convolutions leave Maguire with no choice but to play Peter as such a dippy permanent adolescent that the above torments for the most part don't even register in his brain. Are Stan Lee's heroes as written for the page, as ultimately unplayable as King Leer? An emblem of Spider-Man 3 as good as any is James Cromwell as police captain George Stacy, staring up into the sky, watching his daughter about to plunge to the street, but not reacting at all to surely the most terrifying moment of his life. The bit players chomp and roll their eyes like horses, whether it's through the deadly-pap of Aunt May Life Advice monologues, or the dire, barn-broad, protracted comic relief sequences. Relief from what, exactly? It's a pity to squash it by mentioning it, but in the best joke, Gwen gives a speech before Spidey receives the key to NYC; "I'm here," she boasts, bursting with pride, "because I fell off a building and someone caught me!" There are about seven levels to that line, from sick joke to delightful, and Bryce Dallas Howard's bright, loopy sincerity sounds like a speech bubble is drawn around it.

SM 3: You're pretty well lubricated, you wanna wax poetic about Ms. Stacy some more while I go to the john?

Spider-Man 3 exits to go to the john.

CS: Bryce Dallas Howard naturally glows like a paper lantern, her delicate redhead skin barely diffusing that pale moony luminescence. Raimi can bleach her hair to white-blonde for the role, can shoot her in the flattest attempted four-color comics photography, as if trying to sap all the sparkle out of the woman, so we won't notice the woeful casting of lumpy Kirsten Dunst. But Raimi can't drain the character or the actress entirely, even if he doesn't know what to do with them. Howard's apple cheekbones and square jaw pop off the screen like bold Steve Ditko lines, eyes the blurry green of rolling Irish hills, and rosy complexion shine through the chalky makeup. Bryce Dallas Howard's wide, sculpted nose and lips are the only vivid shaping of space in Spider-Man 3's flat, undimensional New York City.

Spider-Man 3 returns from the john!

SM 3: So you have the hots for BDH.

CS: Yeah, maybe, but she's the only eye-satisfaction to be had. When she's striking poses on a copy machine with the city unfurled in a skyscraper picture window behind her, for a moment, we're looking at a Silver Age splash panel.

SM 3: So the "feel" is right?

CS: The feel is wrong throughout. The tone, the look, the heft and torque are wrong throughout. The side of the building is sheered away, and Gwen slides across the disrupted floor, dangling from a white telephone receiver cord, a simultaneous poor-taste homage to both 9/11 and "The Night Gwen Stacy Died". The movie toys with grandiose icons like this without earning them, without exploration, without understanding them.

SM 3: Those old stories are very silly, and it’s a hard line to walk between classic comics iconography and the emotional heft of serious storytelling.

CS: It’s an impossible line to walk. You have to pick a side. That Silver Age psychedelic fruit punch can't be bottled; the breezy craziness, real-life problems filtered through the wildest spur-of-the-moment giganticized fantasias, they don't lend themselves to streamlining and encapsulation for movies. These worlds don't adhere to the strictures of any other fantasy storytelling logic; they are overfilled with illogic, incompatible rules, the sense that anything goes because only the target audience is reading. The time may have come to accept that the fancy of 12-cent smilin', jolly adventure is necessarily crushed under the pressure of hundreds of millions of dollars.

SM3: So there's no way, you're saying, for a blockbuster Marvel movie to make you happy.

CS: Scale back the budget about 70 percent. Accept the absurdity and let these stories, these characters be themselves. They're being constricted by the mean, watchful eyes of moneymen. Make more Ghost Riders.

SM3: WHAT?

CS: It's the only recent comics movie that embraced its premise, accepted that it is a movie about a flaming skull-head motorcyclist with supernatural powers. Ghost Rider is the best Marvel Comics movie. Every other attempt has been self-important, confused by the reputation that these stories are "classic", or that superheroes are a modern mythology. The perceived naiveté that studios and filmmakers attempt to filter out is the greatest asset of superhero books, birth to Bronze, and it doesn't do to replace it with a gimpy pseudo-sophistication. Steve Ditko drew like a drunk person. His preposterous anatomy and woozy, teetering bad perspective is more key to Spider-Man than making sure than making sure light reflects photorealistically off of costume fabric.

SM 3: Come on, there's all kinds of ridiculous, cornball philosophizing in those books, and nobody would buy it without drastic changes in the tenor of the whole story.

CS: Tobey Maguire’s brittle, unconvincing voice-overs, in which he repeats back to us those lessons we’ve learned from all this torpid drama, on the surface they remind us of Stan Lee’s omniscient narration boxes. The key to those goony text blocks of action play-by-play and enunciation of Today’s Moral, was the surfeit of exclamation points. As Sandman, Thomas Hayden Church, who has the marbled beef-slab face and subsurface malevolence of a '40s gangster movie heavy, is forced to cope with the hoariest invented backstory imaginable: he's doing crime stuff because he has a Sick Daughter. It's a pathetic, doughy attempt to humanize a character, then the movie shovels him into a green striped cartoon costume, and this drama plays out only by having him glance at a his kid's photo once in awhile. By the end, Spidey sends Sandman packing, apparently letting a little girl die rather than allow armored cars to be robbed. Don't get excited for a New York Ripper gut-punch ending, because the movie's forgotten about the dud Sandman motivation.

SM3: But in this story Sandman killed Uncle Ben, and Peter is now endangering a member of Sandman's family, and the new Goblin is avenging his dad. It ties in with the themes.

CS: Sandman killed Ben Parker like Joker killed Thomas Wayne. I plead for a superhero movie moratorium on incorporating your supervillain de jour into the origin story. It's a cheap, transparent ploy to add personal connection to a minor character. Sandman didn't kill Ben Parker. In this series, it's pathetic retconning - why would you need to revise continuity in a series conceived as a trilogy, anyway? - and it doesn't strengthen Peter's ethics quandary as a plot point: it weakens the internal conflict of having killed the carjacker, and the resolution with Sandman on the rooftop is an abstract "choice" for Peter anyhow. He can't defeat Sandman anyway, so there's no choice to make. I mean, there's no where to plug in a vacuum cleaner up there. Oh and for God's sake, an All-Movie Moratorium must be declared on anyone with internal conflict confronting themselves in a mirror.

SM 3: You've confronted yourself in a mirror, haven't you?

CS: Yeah. A lot. (hic) Many times.

SM 3: It's a visual way to express a very non-visual conflict.

CS: It's a yawning chasm of a cliché, and it makes me flash on Glen or Glenda. Speaking of which... amnesia? Really? This is a plot point, that Harry Osborn gets amnesia?

SM 3: What, it's unbelievable? It's a movie about a nerd with wall-climbing powers he got from a radioactive spi--

CS: Genetically engineered spider, asshole. No, it's not the credibility stretch, it's the hackney, contrived stretch. And amnesia, unlike an alien race of gooey symbiotes, is not an invented s.f./fantasy concept. It is unacceptable because it is a broad, dum-dum stroke in a movie that begs for its own gravitas at every other turn. Harry's amnesia, more damning than just an insulting cliché, is a cliché that doesn't serve a function. It doesn't deepen the character, in fact it wipes Harry's slate clean, so that we can't care about this new slap-happy personality-emptied dope wearing James Franco's face.

SM 3: The amnesia makes Harry to forget that he blames Peter for his father's death.

CS: To what ends?

SM 3: It reminds you that you like him?

CS: Then the first movie wasn't doing its job as a trilogy chapter. The point of exploring a villain's motivations is to deepen them as a character and make them more interesting. The amnesia plot prevents that purpose by definition, and amounts to an extended sidetrack from the passing of the Goblin mantle.

SM 3: Well see, Harry's a dark parallel of Peter, they're both driven by family tragedy, and in 3, they slowly switch places, Peter becoming nasty and Harry sunnier, and Mary Jane is the fulcrum between them. And Venom is the catalyst.

CS: Hm. Actually, that's kind of a clever structure... except you forgot: AMNESIA. It must be said. Venom doesn’t fit into this Silver Age Spidey movie, and he can’t be forced. It’s not a character to start with. Venom is a concept and a design for a character, but not actually a character. It's is a bad design anyway, all slimy vinyl and fangs, and no cohesion, like an R. Crumb nightmare woman built only of butts, breasts and legs. The black Spidey suit is a Hot Topic approximation of cool, and if it were an honest design would include a backwards baseball cap and an energy drink in the back pocket.

SM 3: Your preferences are showing.

CS: So I want The Lizard. So I want Stegron. People want Venom, and I accept that. One can only imagine that if you're a fan of the character, this is even more frustrating, because Venom is blatantly shoehorned in. Sorry pal, no Secret Wars movie, no Venom. The symbiote hitches a ride with the Blob and Peter happens to be standing nearby? That's your 300-million-dollar plot point? The hero happens to be nearby one major villain, though the story jumps through hoops to link him to the other two? I was half expecting Stephen King to wander through wearing overalls and holler "METEOR SHIT!"

SM 3: It's a metaphor for the dark side of --

CS: No, it's not a metaphor. As Giles once told Buffy, "I fear the subtext here is rapidly becoming text." It's not a metaphor, because it is made literal throughout. The symbiote literally amplifies Peter's egoism and self-centered tendencies in a story that was already about the deepening divide between lovers as one achieves professional success and the other fails. The venomization is a cheat, because it lets Peter off the hook for acting like a jerk, and it's a cheap story ploy, because he can go back to normal in a snap. On top of that, it's silly, because the symbiote doesn't force out the unpleasant aspects of Peter's personality, it inflicts him with a new asshole-persona: greedy, cruel, shallow. It's additionally not-frightening, because rather than enlarge Peter's flaws, the symbiote makes him dance like Urkel in a prolonged comedy setpiece. It's played for lowest-common-laugh-denominator, not drama.

SM 3: The jazz club scene ends with Peter using a date with Gwen to hurt Mary Jane.

CS: You mean the tango scene from Addam's Family Values?

SM 3: Well yeah.

CS: I don't know what to tell you. For all the scenes of Peter going dorkosexual, which are funny unto themselves, but embarrassing as they are supposed to depict a man in meltdown, why do we never see how the black suit affects Spider-Man while on duty? He smashes Eddie Brock's camera - which we're likely to endorse anyway - and that's it. But man, we need to talk about the validity of this metaphor in the first place. We need to talk about duality and Dark Sides. Because unless those simplistic, dangerous binaries are deconstructed, undermined, complicated: they aren't Grand Themes that add weight to a work by virtue of being mentioned, and if you're trying to tell us something about the human condition, it's nonsense. Spider-Man 3, we need to talk about what you are About. Because you seem to proudly, openly announce a lot of themes.

SM 3: You're not even going to complain about the Osborn family butler?

CS: No. If I learned one thing from Citizen Kane, it's that butlers know things they couldn't possibly know. Don't try to avoid this.

SM 3: With great power comes--

CS: Is that a question, or a statement?

SM 3: No, really: with great power comes great responsibility.

CS: Can we interrogate that slogan? Because Spider-Man, Spider-Man 2 and Spider-Man 3 have all been unwilling to actually complicate that supposedly core idea.

SM 3: Sure, as long as 1) we accept you're being a wiseass, and 2) I'm gonna need another drink.

CS: Proposal 1: "Great power", either in real world terms, and certainly in superhero terms, is not an experience most of us have. It's a means of enforcing the myth that Great Men are separate and burdened in ways the rest of us cannot understand. That's suspect by itself, but damages Peter Parker as an Everyman. Proposal 2: great power and responsibility aren't a bundled two-pack deal, but synonymous. Proposal 3: with every life comes great responsibility. I don't feel the film has a fundamental grasp of this more important notion, and just feels that people in power positions have it real tough.

SM 3: "Even one person can make a difference."

CS: Anyone can make a difference? Or people with great power can make a difference? No one in Spider-Man 3 who doesn't have superpowers makes a difference.

SM 3: Well, MJ throws a cinder block at Venom. Anyway, that's kind of tied to the other theme of how we always have a choice. Like to do good or evil.

CS: And this is supposed to be exemplified by Peter's forgiveness of Flint "Bill Baker" Marko? And/or Harry Osborn going all Han Solo and flying in for a last minute assist in the ending battle royale?

SM 3: This is a trick question, isn't it?

CS: Spider-Man can't beat Sandman. He talks Sandman into floating away because there's no choice left; it's clear that Peter has had a revelation about revenge and forgiveness, which is nice but the decision is made for him. Harry is repeatedly beaten, brain-damaged, facially mutilated by Spider-Man until he has no options but to stop fighting or die. Eddie Brock is covered with alien goop and it's frankly completely unclear how much of a choice anyone has in such a state. At the center of his dilemma, old Double-P is a nice guy at heart, and whether by guilt or sense of duty, obviously feels compelled to fight crime (and as the second movie indicates, when you're Spider-Man, trouble finds you); his biggest choice is essentially made for him. The options are always hardline right and wrong, as a Moral Tale, there's nothing to learn. No tale hoping to illustrate the importance of personal choices should hinge on so many accidents, or present characters with such black and white decisions. Raimi's tactic throughout the Spider-Man films is to make fun of the material he finds silly and quaint, but infuse it with grandiose, reverential announcements of easy moral maxims. In the process, he paints himself as a bigger square than Peter Parker.

SM 3: Oh, also, revenge is a poison.

CS: That it is. Boy, you're sure About a lot of stuff, Spider-Man 3.

SM 3: I'm about more stuff than Ghost Rider. Oh, woah, my spider-sense is telling me you've got a week's worth of transcription here.

CS: Uh, don't swing through traffic in this state. Take a cab.

SM 3: Limo's waiting outside. It's a stretch Hummer!

Exit Spider-Man 3

BRUCE CAMPBELL AS A FRENCH WAITER: Monsieur?

Chris looks at the bar tab.

CS: Sweet Christmas!